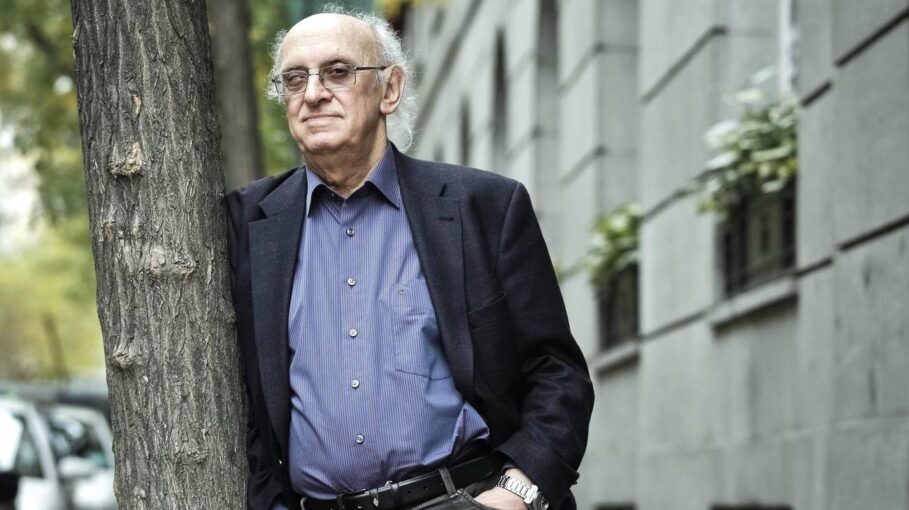

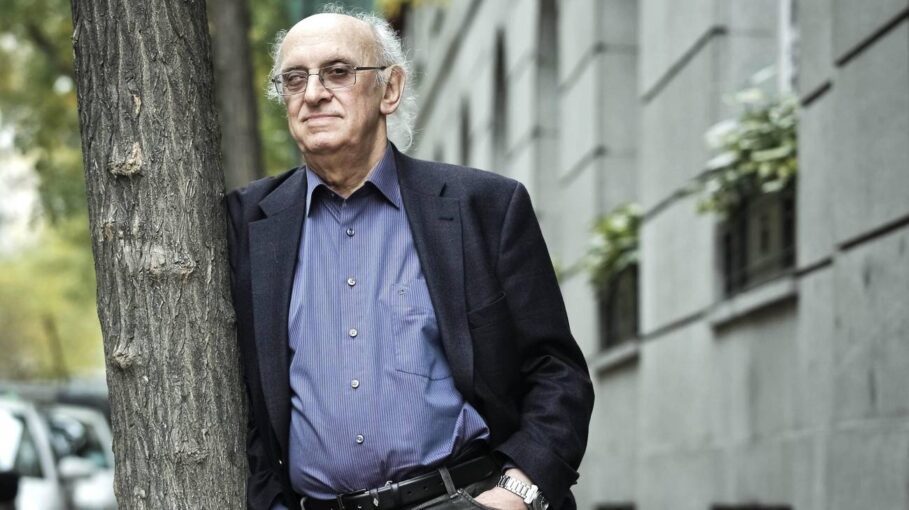

In crime fiction, there are authors/works that every reader feels closer to. For me, Martin Beck or the Wallander series are indisputable. But I have a heartfelt and stronger connection with the three founding authors of Mediterranean crime fiction: Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Andrea Camilleri, and, of course, Petros Markaris. These three writers approached crime fiction as an actual literary genre that had something to say about the world and their country, and of course, they helped to create the school of Mediterranean crime fiction.

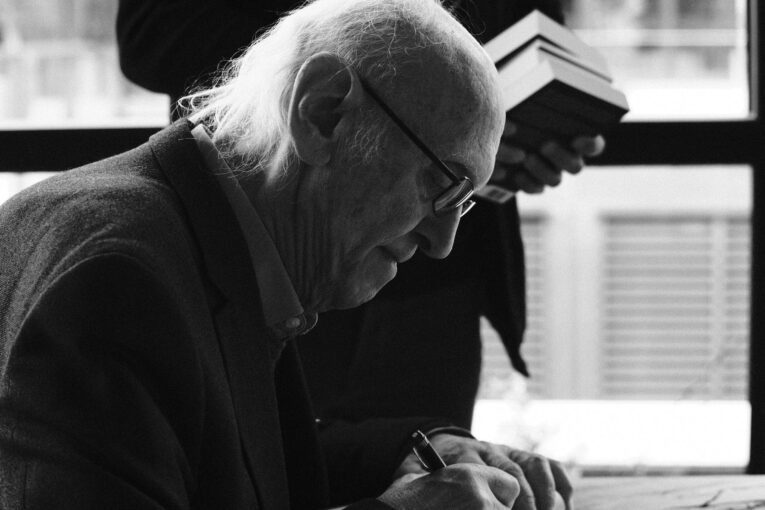

We met with Petros Markaris in Athens, and he was kind enough to host us at his home. For a couple of hours, we talked not only about the Inspector Haritos series but also about the present and future of crime fiction, the crises in the world, and even the present of leftist movements. I learned a lot from this long conversation and thought a lot about it, I hope our readers and crime fiction writers will pursue new questions through this conversation.

First of all, thank you very much for welcoming us to your home and taking the time for the interview. It is a pleasure to meet you in Athens and talk about Inspector Haritos and crime fiction. How did Inspector Haritos come into your life? Let’s start here, if you wish.

Petros Markaris: Thank you very much for visiting me and featuring me in 221B.

I was working in the script team of a series that was aired on TV at the time. I was offered to write another series. I needed money, and my daughter was a child at the time, so I decided to continue. One day, when I was editing the script for the new series, I sat down at the computer and saw a family of three before me. It was like a real family. A woman and a child, I didn’t know that the child was a girl at the time. A very typical Greek petty bourgeois family. I had written so many petty bourgeois characters in the series that I said, “Enough, I don’t want to deal with them anymore.” But the man was stubborn, I saw him in front of me every morning. In the end, it became almost torture. I couldn’t concentrate and work on the script anymore. The producers would say, “What about the script? You’re not sending it.” One day, I said, “If this man is torturing me like this, he is either a policeman or a dentist, nothing else.” I couldn’t do anything with a dentist, so I thought he must be a policeman. That’s how Haritos was born. After I realized he was a policeman, I immediately found out his name, his surname, and his wife’s name. I knew his child was a girl, and her name was Katerina. That’s how the family was born. The vast majority of policemen in Greece are petty bourgeois, and these people cannot live without a family. So, first, I created the family with all its details.

His family also helps us understand Haritos better.

Petros Markaris: Certainly. It also helps to create two different fictions in each novel. On the one hand, crime fiction, and the other hand, the development of the family. Because the family develops. For example, years have passed, and Haritos now has a grandson.

For a long time in world crime fiction, the same type of male cop was written. Lonely, alcoholic, loser, depressed… Haritos also interests me because he represented the opposite of all these when he was first written.

Petros Markaris: You’re right. My character is closer to Simenon’s Maigret. At least Maigret has a job. Haritos has a job and a family. And writing about this family in such detail answered a lot of my questions about petty bourgeois families.

Haritos is very proud of his daughter, for example. He’s probably proud of her because he didn’t get such a good education, and she got a PhD, right?

Petros Markaris: Yes, most of our police are like that. One day, we were sitting in the office of the Greek police chief. I know him very well, and we still talk. When I was writing the novels, he was answering my questions and helping me. One day, I went to visit him again, and we were sitting in his office, and he was answering my questions. The door opened, and a young man came in. The policeman jumped out of his seat, ran to the young man, embraced him, turned to me and said, “Look, my son is going to be a doctor.” He was so proud that his son was going to be a doctor. This is a typical petty bourgeois mentality. That’s why Haritos is so proud of his daughter. Because the previous generation didn’t have the chance to get such a good education, the most important thing in life for them is that their children are better educated, have better professions, and have the possibility of a better life than they do.

It is also very enjoyable to read the bickering between Haritos, Adriani, and their daughter Katerina.

Petros Markaris: All three of them are very witty. I have been traveling to different countries for book promotions for years. Italians and Spaniards are in love with Haritos’ wife, Adriani. They love Adriani more than Haritos. One day, they invited me to a city in Spain called Olot. Olot is 40 kilometers from Barcelona. There was a town hall there from the 16th century. They turned it into a beautiful city library. We were talking to Karme, the director of the library, who is also a very close friend of mine. A woman about 45 years old came in. Karme said, “She is the head of culture in our municipality.” I held out my hand to shake hands with her, but she didn’t even look at my hand. She embraced me and said, “Haritos’ family is just like my family.” I know that all families in Southern Europe are like this. The family ties are very tight. It is like that for Turks, too. The Germans or the French cannot understand this. Their relations with their families are more distant. I say to Germans, “How is Adriani, do you like her?” They say, “She is very good, but she is poor, pity she works so hard, she is always doing housework…”. I say, “Look, if you like Adriani, you will like my mother, they are exactly the same.” This analogy actually started with stuffed tomatoes and peppers, they were my mother’s best dishes. For a long time, I used my mother as a reference when I was writing Adriani. When I write a scene with Adriani, I ask, “What would my mother say? How would she react?” and I write her dialogues with the answers my mother would give. My mother would also always silence my father, just like Adriana did with Haritos.

I wanted to talk about how you create your characters. There are such details and dialogues in your novels that are very realistic and at the same time very unique. In your novels, we come across information about the pasts of the characters and even the pasts of their families.

Petros Markaris: I ponder this a lot. For example, Haritos’ father was a gendarme in the civil war, and this left a deep mark on Haritos. It is very important for me to know what the older generations of the characters did in the country’s past and to think about it. For example, Adriani comes from a very poor family. Epirus was perhaps the poorest region in Greece at that time. This left its mark on Haritos and Adriani.

Perhaps the most curious time in Haritos’ past is the period of the Regime of the Colonels. In the first few novels, we wonder what Haritos did or did not do during this period, you leave it a bit open-ended. But then we learn the details of that, too.

Petros Markaris: Yes, the former leftist character recounts in a novel, “Haritos had just started at that time, and he was on guard at the police station when we were arrested. He always gave us cigarettes. I appreciated that very much,” he says. This is a true story. A leftist friend of mine told me. There was a young policeman who was on the evening watch, and on every evening watch time, he distributed 3-4 packs of cigarettes to the detainees. During the day, leftists were tortured; one of the methods of torture was to hold them in ice-cold water. The same policeman used to take the leftists out on his watch and let them sit next to the radiator so that they could keep warm. I heard all of this from a friend of mine. That was how Haritos was born, from real people like this. When I create a character, I don’t think, “How will it be?” I find a person I know who is suitable for the character I want to create, I create the character according to that person.

For instance, one day, I wrote a scene where Haritos goes into a dress shop and wants to interrogate the owner of the shop because he is a witness to a murder. I wrote the scene and gave it to my sister. I said, “You worked in such a dress shop, look, I don’t want to make a mistake.” She read it and turned to her husband: “She put you in the novel, you’re disgraced!” All the characters I create are like that for me: They are all real people whom I know or whose stories I have heard.

You have also written about Greece’s accession to the European Union and the crises before and after. All these developments are the subject of your novels while they are still happening. How do you determine the themes?

Petros Markaris: I write novels when there is an event, a development in society or politics, or a crisis. I don’t say, “Let it end, and then I’ll write.” I don’t care whether it ends or not. I am supposed to write about the event when it’s happening, and I will. The reason is that sometimes I get so angry at events, at what is happening, that I get infuriated. When I get angry and infuriated, I say to myself, “Petros, now you have to find a story and write a novel; only then can you calm down,” and I sit down and start writing. It has always been like that. Sometimes, when I get very angry about an event or a news story, my daughter says, “Understood, a new novel is coming.”

You write your novels when you get angry, but the concept of distance seems important to me in your novels. You are very familiar with the history and present of Greece, there are truths you defend. But you still approach the issues with a certain distance. I feel this in all your novels, but perhaps most of all in your novel “Long, Long Ago,” which is set in Istanbul. In this novel, you actually write a character who commits revenge killings. But you approach both Greek and Turkish society from an equal distance.

Petros Markaris: Do you know what the most difficult thing was for me when I started writing that novel? My memories from Istanbul were so strong that they were ruining the fiction. I was writing, and a memory would come to my mind, and the fiction would get mixed up. This continued until I found the female character. She was the woman who raised us. The woman who raised me and my sister the most, Maria. Part of Maria’s biography in the novel was the biography of the real Maria. Maria’s end created a situation that was very heavy for my mother. When my sister and I moved to Athens, my mother wanted to come with us, my father didn’t want to move to Athens, but my mother didn’t want to be separated from us, so finally they decided to come to Athens. Maria was more than 90 years old at that time. My mother thought, “A 92, 93-year-old woman cannot start a new life in a new country, she will suffer a lot.” She rented a room in a nursing home for old people so she could live with people her own age. But Maria was very unhappy, and she died unhappy. It was a terrible blow to my mother. She could never forgive herself. So when I thought of Maria, I wanted to at least do something for her. I wrote the protagonist of my novel with her in mind.

You say distance, right, this distance exists in all my novels. I know the German writer Bertolt Brecht very well. I have not only translated his books, but I also know his theater writings very well. I have benefited a lot from him while writing theater plays. Brecht has a theory: “You should always look at things from a distance, you should not become one with the events, and you should never approach the work with emotions.” I know this theory of distance very well. Let’s say something made me very angry, and I started writing, I always look at things from a certain distance, even the event that made me very angry. I never mix my own emotions into it. That’s how I wrote all my novels.

In your crime novels, you make us go deep into the cause of the crime rather than who the murderer is. Why was that crime committed, how does the system lead that person to that crime? We focus on these. I think this is actually a common feature of the “Mediterranean crime fiction” that has developed in Italy with Leonardo Sciascia and Andrea Camilleri, in Spain with Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, and in Greece with your novels. And especially in recent years, I think this common approach of Mediterranean crime fiction has spread to other countries as well.

Petros Markaris: You know, there has actually been a backwards development in European crime fiction. What I mean by this is that today’s European crime fiction is much closer to the 19th-century bourgeois novel. Most 19th-century bourgeois novels start with a crime story: Les Misérables, Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov… So do many novels by Zola and Balzac. All these writers took the crime story as a starting point and wrote realistic novels about their societies. In Mediterranean crime fiction, in addition to describing the life of a society, there is also politics. This started in the 1960s with Jean-Patrick Manchette in France and Leonardo Sciascia in Italy. Then came Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, who wrote about the Franco era, and then Andrea Camilleri in Italy and me in Greece.

Yes, as you said, the basic question has changed. In Agatha Christie novels, the basic question is “Who is the murderer?” In our novels, the basic question is “Why?” and “Why does this person become a murderer?” This is a question of society. When we ask this question, we begin to understand society. On the other hand, how much of a victim is the murderer? How much of a murderer is a victim? The killer-victim issue is not entirely clear in our novels. The best example is the Cuban writer Leonardo Padura. One of Padura’s novels, The Man Who Loved Dogs, is about the relationship between Trotsky and his killer, Ramon Mercader. Padura writes, “Trotsky was the victim, Mercader the murderer who killed him, but Trotsky created the system that gave birth to Mercader. Mercader is a murderer, but he is also a victim of this system.” This question, “How much of a victim is a murderer?” remains open in our novels; it is the same in Camilleri, the same in Montalbán.

I write novels when there is an event, a development in society or politics, or a crisis. I don’t say, “Let it end, and then I’ll write.” I don’t care whether it ends or not. I am supposed to write about the event when it’s happening, and I will. The reason is that sometimes I get so angry at events, at what is happening, that I get infuriated. When I get angry and infuriated, I say to myself, “Petros, now you have to find a story and write a novel; only then can you calm down,” and I sit down and start writing.

“I write novels when there is an event, a development in society or politics, or a crisis. I don’t say, ‘Let it end, and then I’ll write.’ I don’t care whether it ends or not. I am supposed to write about the event when it’s happening, and I will. The reason is that sometimes I get so angry at events, at what is happening, that I get infuriated. When I get angry and infuriated, I say to myself, ‘Petros, now you have to find a story and write a novel; only then can you calm down,’ and I sit down and start writing.”

I think another feature that distinguishes Mediterranean crime fiction from other crime fiction is that the city and its culinary culture almost become the protagonists. This exists in you, Montalbán and Camilleri.

Petros Markaris: Camilleri doesn’t say Palermo, but Palermo is the capital of his novels. Montalbán is Barcelona. And Athens is the home of Haritos. The issue of the city is important, it’s true. Though it is also present in Scandinavian crime fiction. There are writers who describe Stockholm very well, like Arne Dahl. The city has actually become very important for writers like us. In Agatha Christie’s time, it was possible to write stories that took place in a house in the countryside or in a luxurious house. But life is now in the city, and each city has its own uniqueness. It is necessary to write about the city and life there in detail.

And yes, if the first characteristic of Mediterranean crime fiction is that it is socialist and political, the second characteristic is that it includes a lot of cuisine… You see, it is the same with Camilleri, Montalbán, and my novels. After reading a Scandinavian crime novel, I can’t drink beer or eat sandwiches for a week. Nothing there but beer and sandwiches. I get sick of it. But food is very different in our novels.

For example, if you go to Barcelona, even if you speak very proper Catalan without an accent and suddenly say, “I love Montalbán’s novels,” they will immediately understand that you are not Catalan. Because nobody says Montalbán in Catalan, they say Manolo. “Manolo used to eat this and do that,” they would tell you. This culinary issue is also very interesting to Manolo. When I first went to Barcelona, they took me to a restaurant where Manolo used to eat, it was a place called Casa Leopoldo. It’s no longer there, it’s closed because the last time I was there, it had changed a lot, and it wasn’t as good as it used to be. Anyway, Rosa, the owner of the restaurant, came, they introduced me to her, and they said, “Markaris is a crime writer, and he loves Manolo’s novels.” Rosa started telling me her memories of Manolo. Manolo would call her and say, “Rosa, I’m going to have dinner with friends tonight, you’re going to cook these dishes.” he would prepare a menu in his head. Another night, he would call her and say, “I’m coming with friends, I’ll cook dinner.” He was a very good cook. His husband, a university professor, recounted a memoir: “Manolo used to cook a lot of food for me and put it in the fridge before he left for a trip. I don’t like to eat alone at home in the evenings, so I would always go out with friends and eat outside. Manolo would go crazy when he came back and found the fridge full, just as he had left it. He would say, “Am I an idiot, I go to all this trouble to cook for you, why don’t you eat this?” He would start a fight. He was that fond of both cooking and eating…

I am also very curious about your working schedule, you are very disciplined. What is your daily work rhythm like, how long does it take you to finish the novel on average after coming up with the idea?

Petros Markaris: I finish a novel with an average of 6 months of work. I have a very proper working system. I am in front of my computer from 10.00 to 14.00. I continue from 16.30 to 19.30 in the afternoon, every day. I follow this schedule every day, including Sunday. I tell new writers, “Look, if you are an actor and you don’t go to rehearsal, or if you are a director and you don’t go to a shoot, you will get in trouble. No one tells a writer, ‘Sit down and write.’. Therefore, self-discipline must be created. Working hours are the beginning of this discipline,” I say. There can’t be a way of working where I write a scene and then go and have coffee with friends. When you work is up to you, maybe you work from 18.00 to 02.00, but you have to do it every day, those hours must be fixed every day. I have a daily schedule, I have been working like this for years.

The number of crime novels published during the year has increased a lot all over the world, this is also the case in Turkey. What is the state of crime literature in Greece? And what kind of crime fiction is being written?

Petros Markaris: The number of crime writers has increased a lot, that’s true. But there are still those who write novels in the style of Agatha Christie. I try to tell them, “That’s over, don’t bother anymore,” but they still write novels in the style of “Who is the killer?” Secondly, what Germans also like very much is that they want the protagonist, the detective, to be a little bit different, a little bit weird, and I think this has spread to other countries in the world. I say, “There is nothing strange about the police.” If one wants something strange, one can find and create other points not in the police but in the other characters of the novel. Otherwise, if you make an effort to necessarily write the police strange, it would be irrelevant, unrealistic. Don’t try, such a thing will not happen.

For example, my novels are widely read in South America. I know South American crime fiction very well, too. There is only one exception, Ernesto Mallo, an Argentine crime writer, only in his novels the protagonist is a cop. The rest are in the model of the American detective, that is, the protagonist is a private detective, investigator, or journalist, and there is no police. Because these countries experienced dictatorships one after the other. The police were doing the work of these dictators, and the public generally has no sympathy for them. The reader has to establish a very good relationship with the detective or the police. In South America, readers don’t have a very good relationship with the police, they don’t like them. That’s why writers make the protagonist a private detective, not a cop. That’s why I created a very different cop. It was very important for me to create a cop that readers would like. But the police are in love with this different cop, Haritos. They stop me on the road. They ask me, “How is Haritos doing?” My friends say, “Everyone is waiting for your new novel, cops don’t normally read books, but they only read your novels.” I mean, they can empathize with the character, this is very important, so it has to be realistic. Also, the Poirot or Sherlock Holmes type is over. Such characters are neither realistic nor appropriate for our age. Creating something different and distinctive doesn’t happen by making the character different and strange; what could be different is your view of society.

I think this unrealistic character creation has developed partly because of the TV series industry. Many writers now write their novels for TV series or movies. So the focus is on how interesting the character is instead of realism or the actual subject matter.

Petros Markaris: Yes, you are very right. They say, “Let me write it in such a way that it can immediately become a TV series or a movie.” That’s why they write characters that are not realistic, they write characters that are stranger or more old-fashioned. I think this was an era in crime fiction, it’s over. Today, crime fiction is a socialist and political novel, especially in the Mediterranean. But to do that, you need to be political people, or at least you need to be troubled and angry. Andrea Camilleri was a close friend of mine; we used to meet often, and whenever we met, we would talk for hours about what was happening in Europe, in the world, and in politics.

“Now, the basic question has changed. In Agatha Christie novels, the basic question is ‘Who is the murderer?’ In our novels, the basic question is ‘Why?’ and ‘Why does this person become a murderer?’ This is a question of society. When we ask this question, we begin to understand society. On the other hand, how much of a victim is the murderer? How much of a murderer is a victim? The killer-victim issue is not entirely clear in our novels.”

The Haritos series was adapted into a TV series in Greece years ago, is a new adaptation on the agenda?

Petros Markaris: Very few people in Greece know this, but let me declare through you: The Italian producers who adapted Camilleri’s novels into movies are now making a TV series based on my novels. In fact, the filming is taking place in Greece right now.

This is very good news, congratulations. Will it start from the first novel and be shot chronologically?

Petros Markaris: The adaptations of the first four novels will be ready by the end of this year or at the beginning of the next year, and they will release them. First on Rai in Italy, then on Netflix.

Did you work on the scripts, or did you intervene with the screenwriters?

Petros Markaris: Look, I have written so many scripts in my life. I know very well that there is a big difference between a novel and a screenplay. Therefore, a writer who adapts a novel into a screenplay will make changes, he has to, there is no other way. Some of my friends say, “Oh, it changed here!” Of course, it will change; it cannot be otherwise. That’s why I told the scriptwriters, “If you have any questions, I will answer them. If you want an opinion at any point, I will give it. But I don’t want to read or write scripts, that’s your job, not mine.” I don’t want to interfere at all, I don’t find it proper.

You have written theater plays for years, and you also worked with the great director Theodoros Angelopoulos on the scripts of very important films. After years of friendship and colleagueship, you ended your work in cinema when you lost him.

Petros Markaris: Cinema, for me, was only my collaboration with Angelopoulos. His death was a very heavy blow for me. It was an unexpected death, I was devastated, very sad. And I quit the cinema. We were very close friends. We worked together for years. When I say that, it doesn’t mean that we always worked smoothly and sweetly. When I got angry, I would say, “I’m sure you’ll come up with a better idea, so I’ll leave you alone, think about it, and then we’ll talk.” After this conversation, I would go back home and cut contact with him. After 1 week, the phone would ring early in the morning, my mom was alive then, she would answer the phone and she would call me in my bedroom: “Angelopuoluuus…” And he would say to me on the phone, “I don’t accept your objections, but I have a new idea.” This matter of new ideas is perhaps what I will never forget about Angelopoulos. He didn’t try to fix the points we argued on; he threw that idea away and came up with a new one. Sometimes, when he was angry, he would say to me, “We wrote all those scripts together, and you didn’t learn anything from me about the script.” I’d say, “You’re right, but I didn’t have time.” “Why didn’t you have time?” he’d ask. “I was correcting your average scripts; I didn’t have time for anything else,” I would say. The last time we met, we were speakers together at a panel organized at a university in Venice. I told him about this incident and added, “It’s a joke, it’s not serious, let me tell you the serious side, when you read my novels, you won’t see literary chapters in my novels, the chapters in my novels are plan sequences, and I learned the technique of plan sequences from Angelopoulos.” He taught me a lot, not only about cinema but also about literature.

I would like to talk a little bit about Greece. In one of your interviews, you said, “When I first came to Athens, Greece was a country with a very high cultural level, but now it is not like that.” How do you see Greece today?

Petros Markaris: I think this is a problem not only for Greece but for all of Europe. The whole education system has changed. It’s a very bad thing, they are directing all the children towards economics and technology as if they are all going to work in a company, as if they can find a job. Universities that teach social sciences, basic sciences, literature, and art are going bankrupt. The percentage of students studying German literature in Germany is 2%, which is terrible. Parents, children, and politicians don’t understand what a big mistake this is. Now, I’m writing a novel about it. I see it, I go crazy, I write novels, I can’t do anything but talk, tell, and show. I recently read an article in the Observer, it says that in 10 years, there has been a 90% decline in the number of young people studying social sciences, literature, etc. When all these young people go and study economics, business administration, software, etc., we will have millions of young people graduating from the same departments looking for a job, and they will end up working for a slice of bread. They don’t understand, I’m mad about it. In Greece, too, these young people cannot find a job; they all went to similar departments, studied, worked hard, and graduated. Now, most of them are unemployed. I know the same situation exists in Turkey, too. We live in such a world now that the only important thing is money. All other values have been destroyed. There is only one value, and that is money. Can there be such a life? It’s a horrible thing…

How do you see the current situation of the left parties and left movements in Greece and Europe in such an age when all values are being emptied? You have a history of organized struggle in Greece.

Petros Markaris: From 1964 until the dictatorship, I was a member of a left party, the EDA (United Democratic Left). Then all the parties were closed. After the dictatorship, in 1980, I left the party. The reason was that PASOK was in power at that time. One day, my friends wanted to meet me, and we met. “PASOK wants a name from us,” they told me. “What name, I don’t understand?” I said. “He wants names for civil servants,” they said. “We are against this system, we are fighting the system. Now, are we going to benefit from the system, from the state?” I asked. “It is very important that we have people in the state,” they said. I got up and said, “I am leaving now, you will never see me again,” and they never saw me again.

When I look at the European left, I feel depressed, there is not much left. The goal of most left parties in Europe is now only to enter parliament and even to be the government that will ensure the continuation of this order. I have a hard time understanding this.

I exclude the Communist Party of Greece, which received 7% of the votes in Greece, from this. Because they have not integrated into the system, they still manage to criticize capitalism, the system, the government, and the state. This is very important. The Communist Party of Greece did not enter the game that other left parties entered, and did not join them. All other left parties want to be the government within this system.

Andrea Camilleri had also been a leftist since he was a child. He was a member of the Italian Communist Party. He was very close friends with Palmiro Togliatti, who became the general secretary of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) after World War II. We were talking about the same things. Camilleri told me the following story: In the first election after World War II, before the election, a few members of the communist party went to Palmiro and told him that Alcide De Gasperi, who would be the first prime minister of Italy after World War II, would cheat to win the election. Palmiro looked at them and said, “Let him cheat and become prime minister.” The people in front of him were very surprised by this answer. Palmiro explained: “Look, there are two reasons for this. First, if we become the government, this country will go to civil war, I will not drag this country into civil war, I will not do this. Second, we are not a party of the system, we are a party against the system. We should focus on organizing the poor and the workers by fighting the system, capitalism. We do not want to be the government of this system, we are against this system.”

Today, all left-wing parties want to be the government of this system. For example, Syriza did this in Greece, not only Syriza, but many left-wing parties in different countries of Europe started to become social democratic parties. Social democratic parties already existed and exist, so why should left-wing parties replace them? Today, most left-wing parties do not want to destroy the system but rather integrate into it. This is a huge problem.