1. In the Beginning Was the Crime

In the last months of his life, Italian writer Andrea Camilleri reminded us, through the intense pages of his Autodifesa di Caino (Cain’s self-defense, 2019), that crime has existed since the very beginnings of the human race. Not only that – crime is a multifaceted phenomenon, not to be dismissed as simply our dark side or the bad result of a duel between good and evil. Crime is something more complicated, which includes desire, hesitation, deviance, and suffering. Detection, on the other hand, is not as ancient as crime – God’s asking Cain where his brother is, in fact, cannot be taken into consideration since, as Camilleri wittily observes, He already knows where he is and what has happened to him. So any whodunit would have been particularly foregone at the times of Genesis.

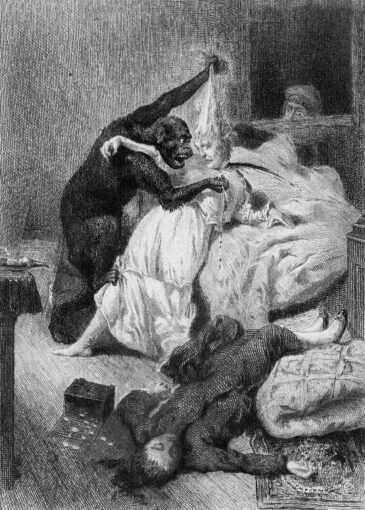

Despite some assertions concerning Voltaire, who according to some critics has given us, with Zadig, “one of the earliest examples of detective fiction, or at least, deductive reasoning” ; in spite of Stephen Knight calling Caleb Williams a “quasi-detective”; and even though I agree with Maurizio Ascari on the enduring legacy of supernatural and gothic forms of proto-detection (2007), we must wait for some time before meeting a real detective in fiction. According to Judith Flanders, the birth of the fictional detective follows the creation of a unified Metropolitan Police Force in London (1829) , and it follows that the first real detective heroes are Mr Bucket (in Bleak House by Charles Dickens, 1852-3) and Sergeant Cuff (in The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, 1868). In the meanwhile, French former criminal and later criminologist Eugène-François Vidocq largely inspired the imagination inside and outside the UK and even across the Atlantic. As a matter of fact, The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe (1841) is generally acknowledged to be the world’s first true piece of detective fiction, since C. Auguste Dupin and his anonymous narrator “laid the groundwork for detective fiction even before the word ‘detective’ had been coined”. Dupin is considered by Stephen Knight as the first literary instance of the investigator as an “intelligent, infallible, isolated hero” (1980: 39) and Christopher Rollason reinforces such a view, regarding him as a master of both scientific and imaginative methods (2000).

Poe, in turn, inspired Arthur Conan Doyle, whose literary creature – the universally known Sherlock Holmes – would carry the weight of the Detective’s role on his shoulders for many years to come. While Dupin was just a good reasoner, however, Holmes, who alternates armchair reasoning in his 221B meditation room with crime scene investigation, is “a prototype for the modern mastermind detective”. Being the first practitioner of what he himself calls the “science of deduction” (which is also the title of chapter 2 in A Study in Scarlet, 1887), he is the first professional detective as well: as he explains to Watson, “I have a trade of my own. I suppose I am the only one in the world. I’m a consulting detective”. It is interesting to add that, in spite of his strong negation of any debts towards Dupin, Holmes makes use of the same logical reasoning, association of ideas, and rational thought. Both characters are children of positivism and their attitude will pave the way to the genre, together with a third character who is seldom mentioned: Paul Somerset, in the Prologue of The Dynamiter (Robert Louis Stevenson 1885), just a couple of years earlier had defined detection as “the only profession for a gentleman”, specifying that its purpose is “to defend society”, “to stake one’s life for others”, and “to deracinate occult and powerful evil”.

At the turn of century, Western society is ready for a spotless and fearless detective who uses his logical skills to fight against evil. But Conan Doyle does not stop there – he gives him a companion, doctor Watson, who is also the narrator of the stories, and by this act he shows a deep understanding of two basic needs of his times – science on the one side, and storytelling on the other. His readership responds enthusiastically.

2. The Rise of the Mass Detective

In the age of mass reproduction and augmented reality, when serial killers challenge serial detectives and TV series challenge Netflix series, it is not difficult to think of the detective as a champion of multiplicity and not of singularity. We have by now become accustomed to all kinds of adaptations, doubles and clones, which continue to multiply thanks to rewriting practices, theatre and movies, serialization, fan fiction, slash fiction, comics, and video games. Nonetheless, there existed a time when, as we have seen, a detective was – or he thought he was – “the only one in the world”. So what happened? And when?

In spite of the assumed rigidity of the “formula”, the figure of the fictional detective has changed continuously in time, according to the literary geography in which he was placed, depending on specific contexts and cultural-political situations, and also owing to the personal choice of different authors. Nonetheless, I believe we can locate a precise moment when the old detective ceases to be what he was, and a new one rises in his place. That moment is when Sherlock Holmes dies at the Reichenbach Falls, in Switzerland, in 1891. It happens in an adventure entitled The Final Problem, which was published in 1893, just six years after Sherlock Holmes’s first apparition in 1887. Rivers of ink have been spilled on Doyle’s tiredness of his own hero (and of detective fiction) and his subsequent surrendering to his furious readership who demanded eternal life for their fictional hero. And right they were, since that was the threshold of a new era. In their opinion Sherlock Holmes could not die, not because of his un-biological nature as a literary character (fictional heroes had always died, from Greek tragedies to the Renaissance and to the Romantic age), but because they (the readers) knew the time had come for them to become an active part of the writing process. Was Conan Doyle unaware of this? Was he really driven by a realistic hope to reach fame thanks to his historical novels? I honestly do not think so. On the contrary, I figure a totally different story.

In my opinion, Arthur Conan Doyle did not decide to get rid of his own creature, as it is generally assumed, but resolved to give him a worthy death – a romantic, glorious, sublime one – so as to make it possible for him to rise again in the new age that was preparing for him. The old Sherlock Holmes, the gentleman detective of the XIX century, really dies at Reichenbach; it is a new Sherlock Holmes, the mass detective of the XX century, who (re)appears in 1894 in The Adventure of the Empty House (1903) to never die again. My hypothesis is supported by the publication, in 1902, of The Hound of the Baskervilles, which was set at a time previous to Holmes’s death but whose publication followed the news of his decease: that is the reason why Doyle chose a totally different scenario for this novel, that is the moors instead of the metropolis, with moonlight vistas in an enchanted landscape, in order to maintain the halo of the sublime around his character.

From that moment on, the mass detective took the place of the former. Next to the already existing theatre, which accounts for a great part of Doyle’s success in the USA, the cinema had made its appearance, first shyly and then more and more aggressively, followed by the radio and then the television; so that it soon became clear that literature should get along with the new media (as it had done with the press and the theatre) in order to survive – and survive great. After that many sleuths were modelled on their predecessors, with obvious exceptions, but they generally obeyed some unwritten rules – which were only codified in the late 1920s – among which the ability to keep a safe position in the minefield of the perpetual conflict between public and private spheres. From the very beginning, in fact, the detective (later called P. I., private eye, in the US) has had to reckon with the social consequences of prying, eavesdropping, snooping around, and asking delicate questions. Whether he was – and is – a private investigator or an officer of public security, the boundaries of his movements, actions, and even conjectures were – and still are – subject to continuous negotiation, redefinition, stopping or trespassing.

Speaking of boundaries, it is worthwhile remembering that we find strong evidence of the normative nature of the genre only during the Golden Age (1920s-1930s), when an obvious need for rules runs across the Atlantic, from The Twenty Rules for Writing a Detective Stories by S. S. Van Dine (1928) in America to the Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction by Father Ronald Knox (1929) in Great Britain. The fact that a whodunit was considered like a game encouraged instructions for use, as some critics argue; but I think that rules were also needed in order to protect the genre from the alien invasions (or cross-contamination) of the supernatural, the sentimental, and all that was not evidence-based. It is thanks to those rules (with due exceptions), no less than to his inner flexibility, that the detective has remained a hero of the secular world, a follower of the scientific method(s), a living combination of logical reasoning and forensics. The Golden Age is now living a revival after years of neglect, and this gives the readers the possibility to both rediscover such detectives as Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot or his companion Hastings from a different perspective (Franks: 22-23), and to delve into books of lesser known authors that have been out of print for years.

With the passing of time, however, many new characteristics emerged in detective fiction since the times of the Golden Age – among which are ethnic and gender issues. More recently, the police station as a community has taken the place of the single detective in many novels and TV series, making the focus shift from individual job to group survey and teamwork; such communities involve an increasing number of female agents and representatives of ethnic minorities and include detectives with disabilities (e.g. quadriplegic Lincoln Rhyme in a series based on Jeffery Deaver’s novels).

3. Out of the Blue, Into the Noir

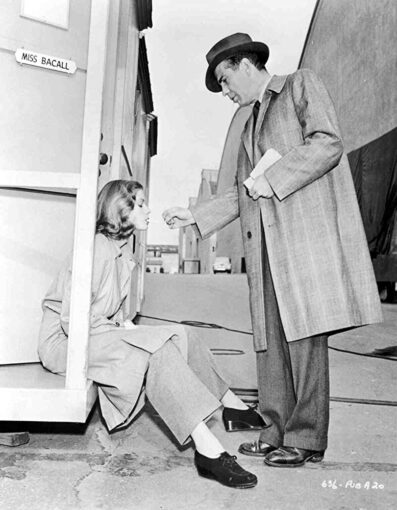

Even though “noir” is an adjective which indicates a precise group of American movies of the 1940s, it is frequently used also as an umbrella term to include detective and crime fiction, mystery, procedural, thriller, true crime, and so on. In this second sense, “noir” can also refer to some crime novels which are not quite whodunits but show some characteristics such as a labyrinthine structure, oneiric vision, vulnerability, urban background, and a generic atmosphere of corruption and chaos. The first group of writers who are recognizably “noir” are the members of the so-called hard-boiled school, from which the film noir will derive. Strange as it may seem, in the same years of the Golden Age, Dashiell Hammett is considered the father of this kind of novel (starting with Red Harvest and The Maltese Falcon, 1929), together with his colleague and friend Raymond Chandler (whose first novel, The Big Sleep, was published in 1939). Their fictional detectives – respectively Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe – represent a totally new kind of investigator, the so-called P.I., whose characteristics are “hyper-masculine toughness” (Gulddal: 36), informal speech, and continuous shifting from moral superiority to involvement in the disorder and decay of society. They are “hard” but more vulnerable than one can guess, a characteristic which will be highlighted in films (see the mirror labyrinth in The Lady from Shanghai by Orson Welles, 1947, or the several beatings in the neo-noir Farewell, My Lovely by Dick Richards, 1975). As Stephen Knight observes, Hammett “first created the adventures of a solitary, honest private detective among the corruptions and betrayals of the modern American city, and Raymond Chandler in the 1930s brought wit and a literary polish” (Knight 2004: 110).

As Chandler wrote in The Simple Art of Murder (1950), this kind of crime fiction depicts a different society and different people with respect to the past and to Europe; in particular, Hammett is different from his predecessors for at least three main reasons: first, because he has “first-hand information” about what he writes, having worked as a detective himself; second, because he takes real people and he “puts them on the page as they are”, letting them speak their own ordinary language; and third, because he “took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley”. This hard-boiled detective “must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man”, a man of honor who is looking for a hidden truth; but, also, “he is a relatively poor man, or he would not be a detective at all. He is a common man or he could not go among common people.”. Of course “common” is a crucial key word.

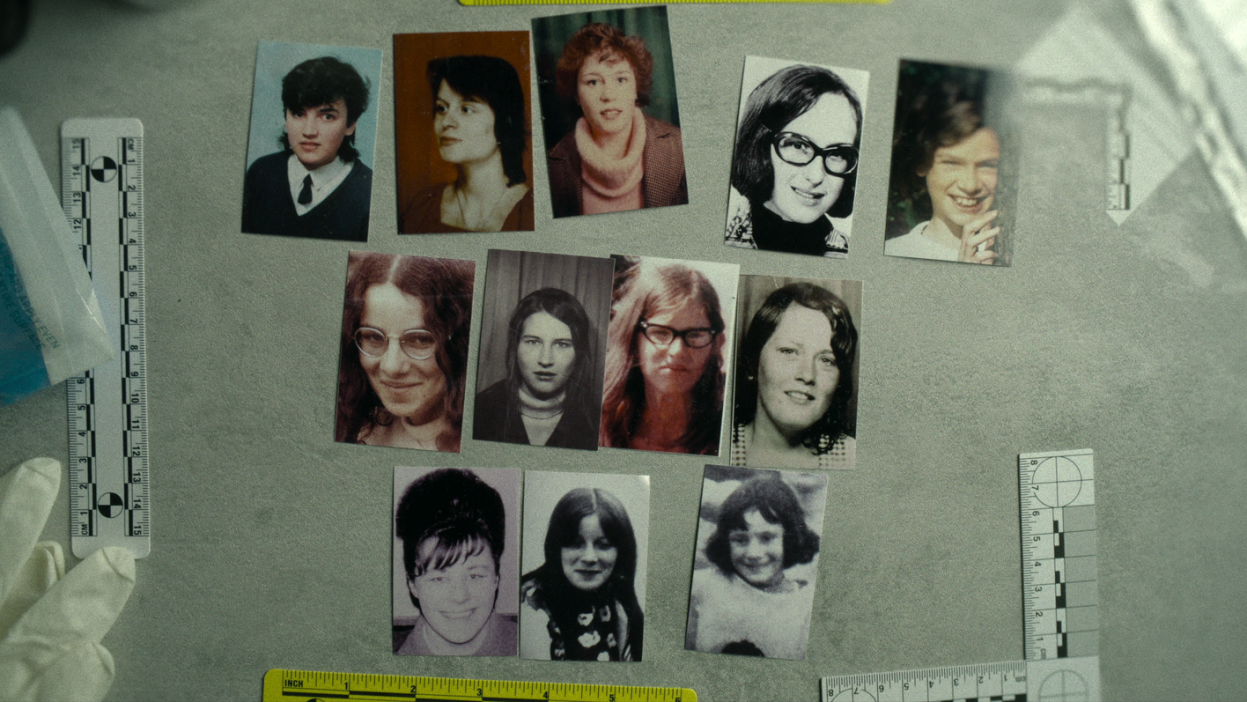

While Rex Stout introduces an experimental mixture of the armchair detective and the hard-boiled P.I. in his Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin series of novels ranging from the 1930s through the 1960s, an almost natural development of hard-boiled fiction is the true crime genre, which derives most of its plots, characters, and themes from real life and crime reports. Its origins are usually connected to In Cold Blood by journalist and writer Truman Capote (1966), who held a personal investigation into the 1959 murders of four members of the Herbert Clutter family in the small farming community of Holcomb, Kansas. Actually, even before Capote, real crimes had either excited the fantasy of writers (see “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt by Edgar Allan Poe”, 1842) or encouraged investigation on the part of writers (see the investigations carried out by Arthur Conan Doyle with regard to the case of George Edalji, 1907, and to the so-called Scottish Dreyfus affair, 1908). After Capote we find many other writers of true crime, among whom James Ellroy, who in The Black Dahlia (1987) tells the story of his own investigation into his mother’s death. Not all examples of true crime are so radical, though.

In the post-modern age the fictional detective acquires a multiplicity of personalities, becoming now sublime (Barbolini 1988), now melancholic (Bertozzi 2008), now one with the reader (Martens 2011), now metaphysical (Darconza 2013), and giving rise to new transcultural and transmedial interpretations (the TV series True Detective, HBO 2014, 3 seasons; the novel Feral Detective by Jonathan Lethem, 2018). Detectives may return from the past and live a new life, such as Philip Marlowe, who appears in Osvaldo Sorianos’ novel Triste, solitario y final (1973), or stem directly as doubles from their own authors, such as “Paul Auster the detective” next to “Paul Auster the writer” in The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster (1987). Also, the detective is interfacing more and more often with disciplines not traditionally linked to humanities, as happens in The Fractal Murders by Mark Cohen (2004), and with post-apocalyptic ecocriticism (see Byrnes 2015). Finally, we cannot ignore the new frontier of A.I., with the post-human detective – a figure already imagined by such early dystopian fictions of the Cold War age as George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighteen Four (1949), Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), and Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report (1956) – becoming a reality thanks to already available programs of predictive policing.

In conclusion, long live the detective, on condition that what Stephen Knight acutely called “Continuities with Change” (2004: 135) continue. And long live detective fiction.