Down These Green Streets is the witty title of a collection of writings on Irish crime fiction by one of Ireland’s leading crime writers, Declan Burke. Paying homage to Raymond Chandler and American hardboiled fiction, the title also stakes a claim for Ireland’s now leading position in global crime fiction. Though that fiction seemed to explode suddenly on the literary world at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Irish crime fiction has a long and sometimes pioneering history that stretches back to the very beginnings of the genre in the nineteenth century. In the process, it reveals itself, in all its variety, as often quite distinct from the English crime fiction within which it was for long subsumed.

Conventionally, crime fiction traces its origins back to Edgar Allan Poe’s three ‘tales of ratiocination’ – ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’, ‘The Mystery of Marie Rogêt’, and ‘The Purloined Letter’ – written between 1841 and 1845. The first story’s celebrated trope of the ‘locked room mystery’ had, though, been notably anticipated three years earlier by Sheridan LeFanu in his story, ‘Passage from the Life of an Irish Countess’, published in the Dublin University Magazine in 1838. The story is more obscure than might be expected mainly because LeFanu revised it as ‘The Murdered Cousin’ (1851), and most importantly incorporated it in one of Victorian Ireland’s best-known novels, Uncle Silas (1865). The publication and transformation of LeFanu’s work tells us much about why Irish crime fiction remained for so long in the shadows. The original story was set, and published, in Ireland but when Uncle Silas appeared as a three-volume novel nearly thirty years later, LeFanu’s English publisher told the author that the book should be ‘of an English subject and in modern times’. The stipulation reflected the fact that the population of Great Britain was some six times greater than that of Ireland, incorporated into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland by the Act of Union of 1800. The financial rewards promised by a much larger reading public long prompted – and continues to prompt – Irish writers to publish in London, despite the recent growth of an important publishing industry at home.

It is easy to see LeFanu’s crime and mystery fiction, including Wylder’s Hand (1864), as having much in common with English mid-century Sensation Novels such as Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1851) or Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone (1868). Even so, LeFanu’s continuing attachment to Gothic tropes allows us to observe that his work – including both Uncle Silas and the vampire novella, Carmilla (1872) – embodies qualities familiar from the nineteenth-century Irish Gothic tradition stretching from Charles Robert Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) – a novel much admired by Baudelaire – to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). Gothic elements remain prominent in the work of Ireland’s leading contemporary crime novelist, John Connolly.

Sheridan LeFanu was first a contributor to, and later proprietor of, the Dublin University Magazine. Magazine publication was important in the development of crime fiction, both through the Victorian practice of serial publication and in the increasing importance of the short story. Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories of Sherlock Holmes in The Strand, beginning in the 1890s, remain the most famous examples but Irish writers also made notable contributions to the developing form. L. T. Meade – penname of Elizabeth Thomasina Toulmin – was a prominent feminist, a pioneer of literature for girls, and author of crime fiction written alone or in collaboration. Meade created one of the most celebrated of early female investigators in the person of Florence Cusack, whose adventures appeared in Harmsworth’s magazine. The much reprinted ‘The Arrest of Captain Vandaleur’ (1894), written with Robert Eustace, is set in London but alludes, via the name of the story’s villain, to some of the most notorious land evictions of the period in Ireland: one of the principal sources of Irish political grievances against England. Together with Dr Clifford Hawkins, Meade also wrote two dozen medical mysteries, first published in The Strand, that challenged male hegemony in the medical profession. Collected as Stories from the Diary of a Doctor (1893; 1895), these stories initiated a still popular sub-genre of crime writing.

The case of Meade’s contemporary M(atthias) McDonnell Bodkin draws attention to the problems of writing in Ireland in the decades immediately prior to the achievement of Irish Independence in 1922. Bodkin was a fervent nationalist whose books included historical fiction concerning attempts to achieve independence for Ireland in the failed 1798 Rebellion. Bodkin’s highly popular detective fiction, originally published in short story form in Pearson’s magazine, was nevertheless set in England. In Paul Beck: the rule of thumb detective (1899) Bodkin created a new type of investigator who, unlike the Great Detective, exemplified by Sherlock Holmes, solves his cases as best he can, anticipating later ‘ordinary’ detectives including G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown and Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple. Bodkin’s crime writing later included novels that also featured Dora Myrl, the ‘lady detective’, and their son, Young Beck, ‘a chip off the old block’. Though forced to abandon a career in medicine, Dora is the personification of the New Woman. Meanwhile, the shift from the short story form to the novel also allowed Bodkin scope to remind readers of his Irish nationalist politics. In The Capture of Paul Beck, Beck and Myrl travel to Ireland on an investigation. It is Dora’s first visit and, though she is familiar with the stereotypical English view of the ‘wild Irish’, she leaves the country ‘a convinced Home Ruler, in love with Ireland and things Irish’.

M. McDonnell Bodkin’s sometimes uneasy attempt to combine his nationalist convictions with success as a writer of popular fiction reveals a much broader problem for Irish crime fiction writers of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Ireland and England evinced very different attitudes towards ‘crime’ and those charged with detecting and punishing it. The Great Famine of 1845-9 and the land evictions of the following decades saw the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) enforce laws that many, in England as well as Ireland, found unjust. The notorious Maamtrasna murders of 1882, when a family of five, including children, were gruesomely slaughtered, resulted in an English-language trial following which one of the defendants, Myles Joyce, was found guilty and hanged, though he was a monoglot Irish-speaker, who almost certainly understood virtually nothing of the proceedings (he was posthumously pardoned only in 2018 by President Michael D. Higgins).

Given the difficulties of writing about Ireland, many writers, besides LeFanu, Meade, and Bodkin, chose to locate their fiction outside the country. Kathleen O’Meara’s tale of intrigue and murder, Narka the Nihilist (1887) is set in Russia and France. Dracula (1897), Bram Stoker’s account of the bloodsucking count is a Gothic invasion novel that moves between Transylvania and England. Exceptional in using Irish settings was Richard Dowling, a former journalist with the Dublin-published nationalist weekly paper The Nation, whose Old Corcoran’s Money (1897) is a dark tale of greed set in a fictionalized Waterford.

Most revealing of all is the still darker story, ‘An Bhean Chaointe’ (1916), by the Irish republican and revolutionary, Patrick Pearse, executed in the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin. A short-story writer in the Irish language, Pearse wrote of a naïve young boy from the west of Ireland, framed for murder by a sinister government agent and a perjured policeman. Here, the author’s sympathy is not for the forces of law and order but for the alleged criminal and his elderly mother, the ‘keening woman’ of the title – a figure drawn from Irish folklore – whose efforts to free her son fail in the face of indifference on the part of politicians both in Dublin and London.

‘The keening woman’ was an Irish-speaker adrift in the alien Anglophone worlds of Dublin and London. Despite the historical importance of the Irish language up to the Great Famine, use of the language declined as Irishmen and women were forced to make their way in English-speaking environments at home or by emigration to Great Britain, the United States, or Australia. The founding of the Gaelic League in 1893 by Douglas Hyde (Dubhghlas de hÍde), later Professor of Irish at University College Dublin, and the first President of Ireland in 1938, gave some impetus to writing in Irish. The Roman Catholic priest Seoirse Mac Clúin took Holmes and Watson as models for Séamas de Barra and his partner Antoine Ó Briain in short stories that appeared in An Sguab [The Brush] in 1922 and 1923. The earliest Irish-language crime novels were Ciarán Ua Nualláin’s Oidhche I nGleann na nGealt [A Night in the Glen of the Madmen] (1939) and Seoirse Mac Liam’s An Doras do Plabadh [The Door that was slammed] (1940). Much Irish-language crime fiction appeared from the state-sponsored publishing house An Gúm, set up in 1926. Best-known among its authors was the English-born Cathal Ó Sándair, whose very popular Réics Carló series, appeared between the 1950s and the 1970s. Whether readers, especially younger readers, should be encouraged to read crime fiction was, however, fiercely debated, for fear exposure to criminal activity might encourage others to attempt it themselves: a view the Irish Censorship Board took in systematically banning true crime magazines between the 1930s and 1960s – though crime fiction was only fitfully banned.

Today’s Irish crime fiction is overwhelmingly written in English but Biddy Jenkinson has written two ingenious Irish-language short story collections, featuring the Jesuit lexicographer and historian, Patrick S. Dinneen, S.J., compiler of the Irish-English dictionary, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla (1904). Others who use the language to engage with modern Ireland include Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, in Dúnmaharú sa Daingean [Murder in Dingle] (2000) and Dún an Airgid [The Silver Fort] (2008), and Anna Heussaff, whose third novel, Scáil an Phríosúin [The Shadow of the Prison] (2015), features a female investigative journalist and a male Garda, disgruntled at being transferred from Dublin to Co. Cork, so engaging with contemporary urban-rural tensions. Heussaff adapted her second novel, Buille Marfach [The Deadly Blow] (2010) into English as Deadly Intent (2014), while Jenkinson, refuses to allow her work to be translated into English: ‘a small rude gesture to those who think that everything can be harvested and stored without loss in an English-speaking Ireland’.

While the language question divided writers at the turn of the century, Ireland’s turbulent politics – the War of Independence (1919-21) against the British, followed by the Civil War (1922-23) – discouraged the writing of crime fiction. Robert Brennan, who led the 1916 Rising in Wexford, wrote fiction that sought to provide entertainment in difficult days, beginning with The False Finger Tip: an Irish detective story (1921), published under the name Selskar Kearney; six short stories set in France, which appeared in the American Detective Fiction Weekly; and the London-published The Toledo Dagger (1927). Among better-known writers, Liam O’Flaherty set The Informer (1925) and The Assassin (1928) in Dublin, shortly after the Civil War, describing the former as ‘a sort of high-blown detective story’, while Frank O’Connor set his celebrated ‘Guests of the Nation’ (1931) in the War of Independence.

To foreground such writers, with their Irish themes and settings, is, however, to distort Ireland’s contribution to crime fiction. Between 1920 and 1957, the influential Freeman Wills Crofts published over thirty novels, and many short stories, which sit at the very heart of Golden Age crime fiction. Dublin-born and Belfast-educated, Crofts spent his early professional life in Northern Ireland, before settling in England, where he co-founded the Detection Club in 1930 with authors including Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers. In The Cask (1920) – published in the same year as Christie’s first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, which introduced readers to the private detective Hercule Poirot – Crofts featured a Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Burnley, in an ingeniously plotted murder case that moves back and forth between London and Paris. Crofts’ most famous character, Inspector Joseph French of the London Metropolitan Police, is notable for being the first fictional police detective hero. Earlier crime fiction, not least that of Conan Doyle, represented policemen as slow-witted and no match for minds such as that of Sherlock Holmes. French, though, is neither Great Detective nor an easily overlooked amateur such as Father Brown. Meticulously plotted, Croft’s novels are frequently and engagingly unpredictable. So, French does not appear until the fourth chapter of Inspector French and the Starvel Tragedy (1927) and is seen only in the second half of Antidote to Venom (1938), an example of the ‘inverted mystery’, in which the commission of the crime, and the nature of the criminal, are the initial centre of interest, with the detective’s attempts to unravel a mystery already known to the reader forming the matter of the second part. A former railway engineer, Crofts was deeply interested in travel of all kinds. Trains, boats, and cars feature variously in the plots of many novels, including The Cask and The 12.30 from Croydon (1934). So do elaborate mechanical devices for the commission of crime, as in Antidote to Venom. Even though Crofts set much of his fiction in England, he often included Irish scenes or sets books partly, or principally, in Ireland, as in Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930).

When Freeman Wills Crofts died in 1957, the style of his novels was a throwback to a departed age. While none of his mid-century successors equalled his renown, they included such notable writers as Nicholas Blake, pen name of the future Poet Laureate, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Nigel Fitzgerald, along with L. A. G. Strong, Sheila Pim, and Eilís Dillon. Between 1935 and 1966, Blake published twenty crime novels, most featuring the amateur detective Nigel Strangeways, reputedly modelled on Day-Lewis’s fellow-poet, W. H. Auden, and set in England. Arguably his best Strangeways novel, The Beast Must Die (1938) later became one of Claude Chabrol’s finest films, Que la bête meure (1969). Born in the Irish midlands, Day-Lewis was taken to England as a very young child but retained close contact with Ireland, and his novel The Private Wound (1968), set in the west of Ireland, suggests the importance to the writer of his Irish roots.

English-born, but with an Irish family background and lifelong interests in the country and its literature, L.A.G. Strong followed in the footsteps of writers like M. Macdonnell Bodkin, writing fine puzzle-mysteries in English settings; featuring Inspector Ellis McKay of Scotland Yard, these ranged from Slocombe Dies (1942) to Treason in the Egg (1958). Nigel Fitzgerald, by contrast, wrote a dozen detective novels, most with Irish settings, featuring Inspector Duffy of the ‘Civic Guard’ – An Garda Siochána – and the actor-manager Alan Russell. Beginning with Midsummer Malice (1953), Fitzgerald’s fiction offers Golden Age puzzle-mysteries, complete – as in his finest work, Suffer a Witch (1958) – with a map of the fictional small town of Dun Moher and a timetable, to assist readers attempting to solve the murder before the detective. Dublin-born and Cambridge-educated, Sheila Pim employed her extensive horticultural knowledge – including the toxic properties of plants – in four crime novels set in an Irish village, starting with Common or Garden Crime (1945) and ending with A Hive of Suspects (1952). The versatile Eilís Dillon, meanwhile, wrote three crime novels employing Irish settings: Death at Crane’s Court (1953), Sent to his Account (1954), and Death in the Quadrangle (1956), set respectively in the west of Ireland; Co. Wicklow; and a Dublin university. While the best of these, Sent to his Account, acknowledges deep-seated tensions between Dublin and the countryside, and in the Wicklow village where a local landowner is murdered, there is little indication of the author’s strongly nationalist sympathies.

Freeman Wills Crofts, Nicholas Blake, and Nigel Fitzgerald were published by Collins, the most influential English publisher of crime fiction; Dillon’s novels appeared from the ‘literary’ house of Faber. In general, though, crime fiction continued to suffer from a belief that it was insufficiently ‘serious’. So, Brian Moore, future author of the greatly admired literary thrillers The Colour of Blood (1987) and Lies of Silence (1990), published seven pulp-fiction titles, including Wreath for a Redhead (1951) and A Bullet for My Lady (1955), under the pennames Bernard Mara and Michael Bryan.

Between the 1950s and 1990s, Irish crime fiction virtually disappeared. Among rare exceptions were writers living outside of Ireland. These included Patricia Moyes author of twenty English-based police procedurals, featuring CID Inspector Henry Tibbett, published between 1959 and 1993 and the journalist and historian Ruth Dudley Edwards who pioneered a return to crime fiction, with a dozen novels featuring Robert Amiss and Baroness Ida (Jack) Troutbeck, from Corridors of Death (1981) to Killing the Emperors (2013). Set in England, these often sharply satirical novels do not entirely overlook Ireland, as in The Anglo-Irish Murders (2000).

Only after decades during which Ireland was characterised by rigid social, cultural, and religious conservatism – along with forced emigration – did Irish crime fiction come to the prominence it enjoys today. Strikingly, modern Irish crime writing draws on an astonishing range of models. Like their counterparts throughout the world, many Irish crime writers have been significantly influenced by the American hardboiled writing that originated with Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross McDonald. However, contemporary fiction also includes police procedurals set in a remarkable range of locations; amateur sleuths; crime comedy; psychological crime novels; historical fiction (set in Ireland and elsewhere); crime fiction for children and young adults; and standalone works that often cross the shadowy boundary between ‘genre’ and ‘literary’ fiction.

Among recent writers, Declan Hughes draws the reader’s attention to the particular influence of the hardboiled. Also a dramatist, one of whose plays explores the relationship between Dashiell Hammett and the playwright Lilian Hellman, Hughes features a detective, Ed Loy, whose name gestures both towards one of Irish literature’s most celebrated (would-be) murderers, Christy Mahon, protagonist of J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World (1907), and Hammett’s Sam Spade (a loy is an Irish spade). Loy features in five crime novels, beginning with The Wrong Kind of Blood (2006), that take the P.I. from the south Dublin suburbs, into the heart of the capital, and on to California. As with Ross McDonald – an important influence – Hughes’s plots expose the hidden secrets of dysfunctional families. Declan Burke’s early crime writing also foregrounds hardboiled influences – particularly Raymond Chandler – in Eightball Boogie (2003) and Slaughters Hound (2013), both featuring Harry Rigby and set in Sligo, in the west of Ireland. Elsewhere, though, Burke’s writing is more notable for its screwball humour, as in The Big O (2007) and Crime Always Pays (2013), while the surreal comedy and metafictionality of Absolute Zero Cool (2011) and The Lammisters (2019) suggest the flexibility of modern crime fiction.

The prolific Ken Bruen reworks the hard-boiled tradition in Irish settings with great élan. The formidable ex-Garda, Jack Taylor, features in over a dozen Galway-set novels from The Guards (2001) to In the Galway Silence (2018) that parody as much as they imitate hardboiled models. Elsewhere, Bruen subverts anodyne English police procedurals with seven novels focusing on his memorably vicious and unscrupulous south-east London policeman, Inspector Brant. Among standalone novels, London Boulevard (2001) is an imaginative reworking of Billy Wilder’s classic noir film. As editor of Dublin Noir (2006), Bruen insisted on the global reach, as well as popularity, of Irish crime fiction.

Hughes, Burke and Bruen transplant American hard-boiled writing to Ireland. Other work, notably by women writers, is of an equally gripping, though less overtly violent, kind. Arlene Hunt’s False Intentions (2005) is the first of five novels featuring QuicK Investigations – the Dublin partnership of John Quigley and Sarah Kenny – that engage with contemporary Irish social issues in popular form, exposing corruption behind the façade of middle-class respectability. Two later books, The Sweetheart Killer (2018) and Last Goodbye (2018) concern investigations by Dublin police detectives Eli Quinn and Roxy Malloy.

Among the first contemporary writers to introduce police officers to Irish crime novels was Hugo Hamilton, in Headbanger (1996) and Sad Bastard (1998), two blackly humorous works featuring the headbanging sad bastard Dublin Garda Pat Coyne, which, at the outset of the Celtic Tiger years, combined exposure of Irish criminality of different kinds – including gangsterism and clerical child sexual abuse – with an interrogation of the increasingly hybrid nature of modern Irish identity. Subsequent Garda Síochána officers have included Niamh O’Connor’s Dublin-based DS Jo Birmingham and Julie Parsons’s (retired) DI Michael McLoughlin, most recently in the intricate and powerful The Therapy House (2017). Novels featuring Jim Lusby’s DI Carl McCadden from Waterford, Brian Gilloway’s Inspector Benedict Devlin of Lifford, and Dervla McTiernan’s DS Cormac Reilly from Galway take modern Irish police fiction out of the capital into the provinces.

Among the very best, and most widely praised, works dealing with police detectives, are six novels by Tana French, featuring different members of the Dublin Murder Squad, and set in a revealing range of locations in and around the Irish capital: the south Dublin suburbs, the inner-city, a bleak estate on Dublin’s northern fringes, and an expensive south Dublin girls’ school. Imaginative, complex, and stylistically confident, these novels feature different police investigators, including Detective Cassie Maddox of The Woods (2007) and The Likeness (2008) and detectives Antoinette Crowley and Stephen Moran of The Secret Place (2014) and The Trespasser (2016). The shift is a notable strength of French’s books and one possible solution to the risk, experienced by all writers of crime series, of uncritical repetition. Nevertheless, French’s fiction is underpinned by shared themes, including friendship and family, central also to French’s standalone novel, The Wych Elm (2019; US title, The Witch Elm, 2018). French’s work also engages with the difficulties experienced by female officers of sustaining both a personal and a professional life, especially in an environment so traditionally hostile to women as the police service. A similar concern runs through other crime fiction by women including Sinéad Crowley’s novels featuring the married Detective Sergeant Claire Boyle in Dublin and Jane Casey’s London-based fiction, from The Burning (2010) to Silent Kill (2020), in which Detective Constable (latterly DS) Maeve Kerrigan’s ambivalent feelings towards her policeman live-in boyfriend, Rob, and her partner, the thoroughly misogynistic DI Josh Derwent, complicate her feminist ideals.

If Irish crime fiction of the nineteenth century differed from that of England because of very different perceptions of policing, something similar was long true of the difference between crime fiction written in the Republic of Ireland and in Northern Ireland. In four novels written in the 1990s, Eugene McEldowney, the Belfast-born former assistant editor of the Irish Times, writes of Superintendent Cecil Megarry, who serves in the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in Belfast. While highlighting the godfathers of violence, McEldowney’s work is notable for its clear-eyed but sympathetic evocation of a society in which almost everyone is, in some way, a victim of the unresolved political situation. The political shift that followed on the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that largely brought to an end ‘the Troubles’ – the sectarian violence that had disfigured the life of Northern Ireland since the late-1960s – is reflected in the sympathetic depiction of Stuart Neville’s Inspector Jack Lennon and Brian Gilloway’s DS Lucy Black, who both serve in the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), which replaced the discredited RUC in 2001.

In exposing unwelcome truths about modern Ireland, crime writers have necessarily confronted its past. Nineteenth-century Catholic distrust of the RIC and late-twentieth century republican hatred for the RUC militated against the writing of police procedurals. Several novelists have recently attempted to explain, and fill, this void in historical crime fictions. Conor Brady, former editor of the Irish Times, member of the Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission (2005-11), and author of histories of the Garda Síochána, has written four well-researched novels – A June of Ordinary Murders (2012) The Eloquence of the Dead (2013), A Hunt in Winter (2016) and In the Dark River (2018) – featuring Sergeant Joe Swallow of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, and touching on events including Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, land evictions, and the fall of the nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell in 1891. Kevin McCarthy has done something similar for a later period and a different location, the War of Independence in Co. Cork, in Peeler (2010), whose central character, Acting Sergeant Seán O’Keeffe, reappears in Irregulars (2013), set during the Civil War. Adrian McKinty’s outstanding DI Sean Duffy series features a maverick Catholic officer in the overwhelmingly Protestant RUC in the 1980s. Unlike Megarry, Duffy is partly cast in the hard-boiled private eye mould. Yet while the stubbornly insubordinate fictional detective takes refuge in drink and drugs – enlivened by a stimulatingly eclectic taste in music – Duffy’s particular demons arise precisely from his being among a small minority of Roman Catholic officers during the Troubles: a minority often despised, even by Protestant fellow officers. With his black humour and sharp intelligence, Duffy is a truly memorable character in six novels with Tom Waits-inspired titles, from Cold, Cold Ground (2012) to Police at the Station and They Don’t Look Friendly (2017).

The Troubles in Northern Ireland did not generally prove conducive to writing crime fiction. Yet exceptions are to be found in works as varied as Benedict Kiely’s Proxopera (1977), Bernard MacLaverty’s Cal (1983), and Brian Moore’s Lies of Silence. Pioneered by Eugene McEldowney, Eoin McNamee and Colin Bateman, contemporary writing finds its origins in the years between the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 and the Good Friday Agreement. The difficulties of writing crime fiction constructed around police figures is indicated in a Northern Irish context by the work of the comic crime writer, (Colin) Bateman. Fiercely funny and exceptionally prolific, Bateman has written just two such novels, Murphy’s Law (2002) and Murphy’s Revenge (2005) – based on a TV series he created – featuring an undercover policeman who, following the death of his young son in an IRA bombing, is reassigned to London. Bateman’s other fiction is notably wide-ranging, comprising both series and standalones such as Mohammed Maguire (2001), which offers an outsider’s bleakly comic perspective on Northern Ireland. Readers of crime fiction have often fought shy of comedy, even black comedy, but Bateman’s is a major and distinctive voice in contemporary Irish crime writing.

Among younger writers, Stuart Neville created Inspector Jack Lennon, who features in four fictions set in Northern Ireland, published between 2009 and 2014. Neville later added a new series whose central character is Lisburn-based DCI Serena Flanagan. Despite the presence of Lennon, the real focus of Neville’s outstanding, gothic-inflected debut novel, The Twelve (2009), is Gerry Fegan, a republican paramilitary killer, haunted by the ghosts of the twelve people he has murdered: soldiers, members of the Ulster Defence Regiment, the RUC, loyalist paramilitaries and four civilians, ‘in the wrong place, at the wrong time’. Fegan hopes to exorcise his demons by killing the godfathers of the crimes he has committed, against the background of a Northern Ireland slowly changing after the Good Friday Agreement. The past, though, will not go away: ‘it was the civilians whose memories screamed the loudest’.

Brian McGilloway’s first five novels, beginning with Borderlands (2007), concern Garda Detective Inspector Ben Devlin, who lives in Lifford, Co. Donegal, in the Republic of Ireland. Across the River Foyle, is Strabane, Co. Tyrone, in Northern Ireland, home to the PSNI’s Inspector Hendry. The books, then, literalize the idea that crime fiction’s defining location is a liminal zone. The border here, the novels suggest, is an arbitrary one–as indeed it was–and as easily crossed by post-Troubles criminals as by paramilitaries. The lack of cooperation between the Garda Síochána and the RUC in the decades before the Good Friday Agreement is seen as gradually, if uneasily, improving as the peace process slowly progresses. A more recent series, set in Northern Ireland, features DS Lucy Black of the PSNI, but in his latest work, including The Last Crossing (2020), McGilloway seems increasingly to be traversing another disputed border: that between genre and ‘literary’ fiction.

In six novels, most recently The Killing House (2018), Claire McGowan also writes of the PSNI though her protagonist is the forensic psychologist Paula Maguire. In The Dead Ground (2014), Maguire’s life seems to be falling apart when she discovers herself to be pregnant. Its plot constructed around cases concerning missing children and the murder of a lesbian doctor who runs a family planning clinic, this London-published novel confronts English readers with the notion that, in legal, moral, and political matters, the idea of the United Kingdom is a fiction. In Northern Ireland, abhorrence of abortion and homosexuality unites otherwise divided hardline republicans and unionists. The daughter of a Catholic policeman father passed over for promotion in favour of a less competent Protestant, with whom she now works, and of a mother who remains one of the ‘disappeared’, Maguire must unwillingly accept the need for, and inevitability of, compromise in personal as well as political life.

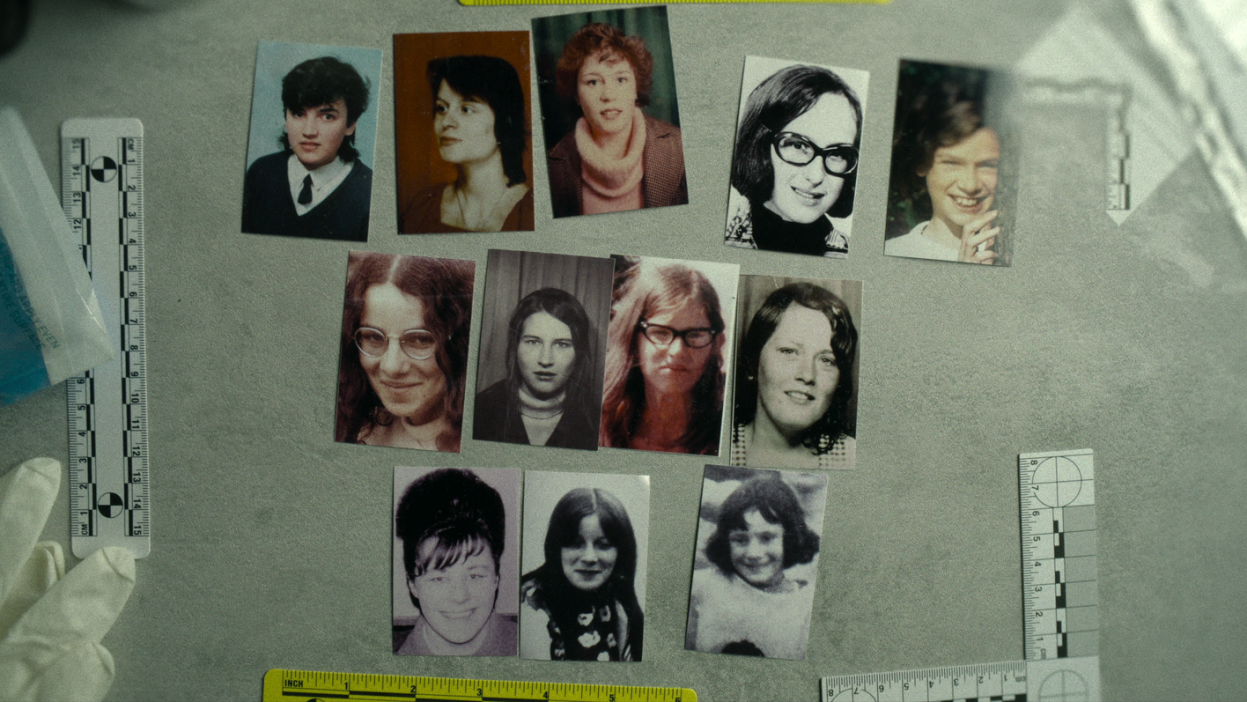

The best known, and arguably the best, crime fiction writer from Northern Ireland is Eoin McNamee. Resurrection Man (1994) is a chilling, lightly fictionalized account of the Shankill Butcher murders of 1975-82, in which a small group of Protestant killers, led by Lenny Murphy (reimagined here as Victor Kelly), snatched random Catholics, or those they believed to be Catholics, from the streets to beat them before cutting their throats. Never gratuitously brutal, Resurrection Man is an unflinching portrait of a psychopathic killer trapped in the inescapable sectarian topography of Belfast. What is most distinctive about McNamee’s fiction, perhaps, is the determination to expose the realities of a Northern Ireland troubled long before 1969. The ‘Blue’ trilogy offers different perspectives on the life of Lancelot Curran, a real-life Northern Ireland High Court judge, Ulster Unionist MP, and father of Patricia Curran, a nineteen-year old student murdered in a frenzied knife attack in 1952. The Blue Tango (2001) revisits that murder, and the resulting miscarriage of justice that led to the conviction of Iain Hay Gordon in 1953 (cleared of the crime in 2000). The trial of Robert McGladdery for the murder of a nineteen-year old woman is the focus of Orchid Blue (2010); the judge was Curran, who passed sentence of death on McGladdery who, in 1961, became the last person to be hanged in Ireland. Blue is the Night (2015) returns to an earlier murder case in which Curran was prosecutor, allowing the backroom machinations designed to ensure the prosecution fail – in order not to endanger Curran’s emerging political career – to expose the corruption endemic in the stultifying Northern Ireland of the 1950s. The extent to which Northern Ireland is now a recognized location within the world of modern crime fiction is suggested by the fact that Belfast Noir (2014), edited by Adrian McKinty and Stuart Neville, has joined Dublin Noir as part of the well-known international series.

Eoin McNamee’s writing owes much to genre fiction but refuses to be contained within it. Among similarly evasive works are John Banville’s The Book of Evidence (1989), Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy (1992), William Trevor’s Felicia’s Journey (1994), Joseph O’Connor’s The Star of the Sea (2004), Aifric Campbell’s The Semantics of Murder (2008), Emma Donoghue’s Room (2010), and Neil Jordan’s The Drowned Detective (2016), three of which are based on real-life cases. Carlo Gébler, too, has used historical crimes as the basis of unconventional novels whose titles, including How to Murder a Man (1999), consciously evoke crime fiction. The Dead Eight (2011) persuasively reworks events leading up to the 1940 murder of Mary McCarthy in Tipperary and to the hanging of an innocent man, Harry Gleeson (granted a posthumous pardon by President Michael D. Higgins in 2015). Here, the crime and its (known) outcome are related only close to the end of the novel, whose focus is on social, religious, political and sexual tensions within the repressed rural society of the 1920s and 1930s.

Like Gébler and others, Joe Joyce, in three Echoland novels (2013-15) located in Ireland during the ‘Emergency’ (Ireland’s euphemism for World War II), and Benjamin Black (pen-name of John Banville), in his popular series featuring the consultant pathologist Quirke, set in 1950s Dublin, have sought to bring the Ireland of the past into modern crime fiction. Meanwhile, a focus on the still important phenomenon of organized crime in Dublin characterizes four novels by Gene Kerrigan: from Little Criminals (2005) to The Rage (2011). The unblinking focus on an urban underclass that middle-class Ireland would prefer to overlook owes much to the author’s experience as a crime journalist and author of admired true-crime books, and Kerrigan has described his own fiction as paralleling shifts in Irish society that occurred in the opening decade of the twenty-first century. While Kerrigan has asserted that ‘Crime is often a distorted version of the behaviour held in high regard within a society’, the wide-ranging columnist and literary editor of the Irish Times Fintan O’Toole opined that ‘Irish-set crime writing … has arguably become the nearest thing we have to a realist literature adequate to capturing the nature of contemporary society’.

Crucial to Irish experience, and the expedition of social change, in recent decades has been the investigation of long-standing cases of often deliberately repressed injustice: domestic violence against women and children; child abuse by priests and other religious; the enforced adoptions of children born out of wedlock and the confinement of their mothers, and other unfortunates, to Magdalene laundries run by the Roman Catholic church; violence against young children in Industrial Schools; the expanding gang-controlled drug and sex trades, along with widespread financial corruption extending through the worlds of politics, banking, and property. The link between crime and the unrestrained capitalism of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ years – c. 1994-2007 – also informs Alan Glynn’s prescient Winterland (2009), which eerily foresaw the slump that followed. Glynn’s later novels, Bloodland (2011) and Graveland (2013), rehearse the theme of corporate greed while extending their range beyond Ireland to the United States and Africa, in what the writer called his ‘globalization’ trilogy.

Globalization has, inevitably, changed Irish crime fiction. The Irish diaspora underpins Adrian McKinty’s Michael Forsythe trilogy, starting with And Dead I Well May Be (2003), whose hero, an illegal immigrant escaping from murderous paramilitaries in Northern Ireland, soon falls foul of equally murderous criminals in the United States. In her impressive debut novel The Fall (2012), Claire McGowan offered a stark picture of contemporary London, divided by class and racial mistrust. Yet the literary marketplace remains important, as it was for London-bound Irish writers of the nineteenth century. Though the success of Irish writing has led publishers, including Penguin and Hachette, to set up Irish subsidiaries, many writers discussed above publish in England. The lure of a wider readership has led to authors using international settings. William Ryan’s Captain Alexi Dimitrevich Korolev works in the USSR of the 1930s, and Conor Fitzgerald’s Commissario Alex Blume in modern-day Rome. Ken Bruen in three novels, Benjamin Black in The Lemur (2008), Eoin Colfer in Plugged (2011) and Screwed (2013), and Arlene Hunt in The Chosen (2011) are among those to have set works in the United States. Alex Barclay, whose two Joe Lucchesi novels feature an NYPD detective transplanted to Ireland, later moved in the opposite direction, with the Denver police detective, Ren Bryce, featured in five novels from Blood Runs Cold (2008) to Killing Ways (2015).

That today’s writers no longer fear to expand their horizons beyond the island of Ireland is most evident in the prolific work of the most successful contemporary Irish crime novelist, John Connolly. In a compelling series of eighteen novels, from Every Dead Thing (1999) to The Dirty South (2020), featuring the former NYPD cop, now P.I., Charlie Parker, Connolly deploys a distinctive prose style, at once richly allusive and capable of great poetic force. Most particularly, Connolly’s pervasive use of Gothic tropes suggests close affinities with Irish predecessors, going back through Bram Stoker and Sheridan Le Fanu to Charles Robert Maturin. The setting of the Charlie Parker series in Maine reminds readers that, from Poe onwards, crime fiction has inhabited borderlands. Maine is a liminal zone, not only the most northerly of the United States, bordering on Canada, but a maritime state, whose main settlements lie on a heavily-indented Atlantic shoreline, while its largely uninhabited interior is a space where civilization and untamed nature coexist uneasily. Parker remains tormented by his failure to protect his wife and child, murdered before the series begins, and throughout Connolly’s fiction past and present are woven inextricably together. The spectral presence of sinister figures like the Travelling Man or the Collector, who cross time and space, opens up the novels’ sharply realistic depiction of contemporary settings to a more expansive, timeless engagement with the origin and nature of evil. Such fundamental questions seem sometimes to embarrass writers of contemporary crime fiction. Connolly, by contrast, demands the reader face them both by means of compelling and unsettling narratives and by the skilful deployment of epigraphs and mottoes, including one from Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita which opens A Song of Shadows (2015): ‘What would your good do if evil didn’t exist, and what would the earth look like if all the shadows disappeared?’. Seeming to have turned its back on the Ireland so variously represented by the writers discussed above – and many more – Connolly’s haunting work, shot through by deep-rooted religious and racial hatreds, forces readers of popular fiction to confront the buried truths of Irish history and the still pressing need to come to terms with them.