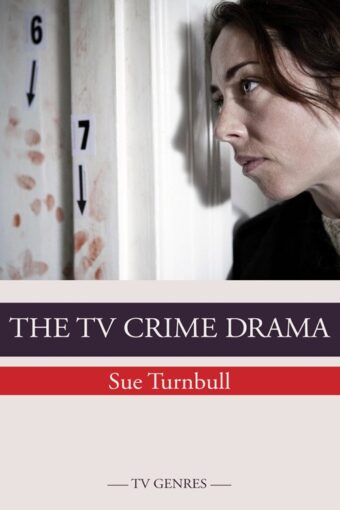

In Sue Turnbull’s volume The TV Crime Drama, an entire chapter titled “Women and crime” is dedicated to the relationships between the genre and gender issues, and in particular the question of gender equality. “Despite a perception that the television crime drama may be an inherently ‘masculine’ genre”, writes Turnbull, “women have played a key role in television crime drama right from the start, not just as the helpless victim or the untrustworthy femme fatale, but increasingly as a major player in the unfolding investigation and always as a potential member of the television audience at home from the 1950s to the present day”.

Besides, Turnbull continues, “the portrayal of women in the crime drama series has served both as an index of women’s changing role in society while providing a catalyst for debate both in the popular press and in the field of feminist media studies”. As also stressed by Megan Hoffman in her Gender and Representation in British ‘Golden Age’ Crime Fiction, female characters in the crime genre allow understanding how gender and genre norms are questioned and re-negotiated within the wider social context.

Historically, women as characters, authors and consumers have played a very important role in crime fiction – and indeed, more relevant in literature than in film and television. This role has been largely discussed by a wide scholarly literature that helps us to better explain both that perception of the “inherently” masculinity of a conservative genre like crime, dominated by the re-establishment of an original balance jeopardized by the criminal act, and the relationships between female representation in the genre and changes of female condition in the wider socio-cultural context, and especially in the workplace and in domestic spaces.

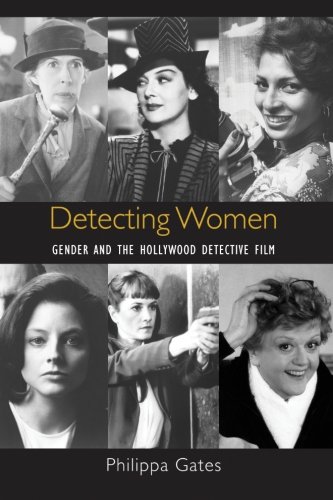

As Philippa Gates argues in the book Detecting Women: Gender and the Hollywood Detective Film, “key conventions of the female detective are established at the end of 1800. The problem with having a female heroine at the center of a detective story at this time was how to reconcile traditional notions of femininity with the perceived masculine demands of the detective plot”. Kathleen Klein, in her The Woman Detective: Gender & Genre, addressed the problem of the intersection between gender and genre through the notion of “script”, underlining that “the script labeled detective in readers’ minds did not naturally overlap or even mesh with the labeled woman”. In The Female Investigator in Literature, Film and Popular Culture, Lisa Dresner expanded this perspective, suggesting how detective’s qualities are traditionally and culturally coded as masculine, “either the hyper-rationality of the intellectual detective or the casual violence of the hardboiled detective”. In this respect, the “female investigator is presented as fundamentally flawed [and] serves as a marker of the incompatibility of the cultural categories of woman and detective”.

More precisely, studies on crime fiction have shown that the possibilities of having a fulfilling sentimental life and carrying out a detection activity (especially at a professional level, and not only as an amateur) are traditionally considered as mutually exclusive, at such a point that Gates recognizes that the female detective must struggle “to be both a successful detective and a successful woman”. Of course, “success” for a woman must be interpreted in relation to the prevailing social definition of female identity in connection with the roles – socially prescribed but perceived as “natural” – of wife and mother.

Unless she is too young (Nancy Drew) or too old (Miss Marple or Jessica Fletcher) for romantic relationships, the woman detective is often single, divorced or widowed – in any case, alone. However, as Maureen Reddy shows very well in her contribution to The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction, “solitariness for a woman has far different meanings than does solitariness for a man, as historically women have been defined by their relationships with men. […] Solitariness of female detectives is not presented as a badge of honor but as a condition dictated by prevailing gender definitions”. The lonely female investigator, without marriage and family, tends to be perceived – like her criminal counterparts – as an “unnatural”, incomplete, or at least unusual woman. As Gates points out: “There is something unnatural about the woman who denies the socially prescribed but perceived as natural roles of wife and mother”.

Turnbull’s investigation into the presence of women in TV crime drama virtuously combines the two perspectives “behind the camera” and “on-screen”, and analyzes in detail the female presence in productive and creative roles. However, this analysis is limited to US and UK, with the only exception of the Scandinavian territory, which is included to examine the well-known characters of Sarah Lund (The Killing, 2007-2012) and Saga Norén (The Bridge, 2011-2018) considered as the legitimate heirs (“the true daughters of Jane Tennison”, Turnbull writes) of the progressive models of female detective proposed by TV series such as Cagney and Lacey (CBS, 1982-1988) and Prime Suspect (ITV, 1991-2006)

The first is particularly important for the great creative role accorded to women in production, writing and direction, and for the break with the traditional TV models of the detective woman as an object of desire: the two detectives are both in their 40 and are mostly dressed in comfortable working clothes. The second, written by Lynda La Plante, has a pivotal role in establishing an innovative and progressive model for female detection. The show stars Helen Mirren as Jane Tennison, Detective Chief Inspectors in Greater London’s Metropolitan Police Service, and stresses her everyday struggle with the institutionalized sexism in the police force

For many European countries not included in Turnbull’s analysis, however, original researches combining on-screen and off-screen perspectives to investigate women in the crime genre, both as creators and characters, are still missing. From a pan-European perspective, investigating women in the TV crime drama can play an essential role not only to understand the evolution and main trends of the genre. In the framework of the European research project “DETECt”, it can also help understand how popular crime narratives contribute to the emergence of a transcultural European identity, from both a top-down and a bottom-up perspective.

From a “top-down” perspective, policies in support of gender equality are an important area of commitment in the European Union’s agenda and they establish a set of shared values, with enormous potential for aggregation and identity. From a “bottom-up” perspective, European identity can only be understood as a space of interaction and dialogue between multiple forms of identity: cultural, social, national, local and, indeed, gender identities. In this sense, the challenge of the “woman detective”, traditionally problematic in the light of both gender and genre norms, and the different solutions proposed in different cultural contexts of the continent, can tell us a lot about the formation of a plural and shared identity.

In this article, I will provide a contribution to this broader research by focusing on the Italian context and some recent productions featuring a woman in the role of investigator.

In general terms, Italian most successful (both nationally and internationally) crime TV series seem to have been mainly related to two models, the male-based one and the team-based one, where women can play more or less significant roles, as in other, well-known international cases such as Law and Order, NCIS or CSI.

The most popular productions of the public broadcaster Rai include the TV adaptation of the literary character Salvo Montalbano (Il commissario Montalbano / Inspector Montalbano, 1999-), a police inspector based in the imaginary small town named Vigata and created by the Sicilian writer Andrea Camilleri, and Don Matteo (2000-), which presents a priest in the role of an amateur detective. The commercial broadcaster Mediaset has instead preferred the team-based model, telling the stories of different investigation teams belonging to Italian military forces: Distretto di polizia (Police District, 2000-2012), Carabinieri (2002-2008) and RIS (Crime Evidence, 2005-2009).

Within such a traditional and conservative scenario, both in the approach to the forms of the crime genre and in the use of serial narrative forms, the pay-tv player Sky has played a groundbreaking role. In addition to distributing in Italy the most interesting outcomes of “quality” or “complex” TV developed abroad especially by HBO, since 2008 it started to produce original TV series that reworked the genre both at a narrative and thematic level.

In 2008, Sky produced its first crime TV shows. The first was the popular success Romanzo criminale, inspired by the novel by Giancarlo De Cataldo that was also the basis for the film by Michele Placido in 2005, which re-proposes the team-based model in a completely masculine version, focusing on criminals as anti-heroes. The second was Quo vadis, baby ?, co-produced with Colorado Film and inspired by the work of the female writer Grazia Verasani, that was also the basis for Gabriele Salvatores ’movie in 2005.

Quo vadis baby? is about the investigations of the female private eye Giorgia Cantini, interpreted by the indie-rock singer and actress Angela Baraldi. The character represents a clear attempt to rework the classic hardboiled detective: she is single, about 40 years old, has no children and lives in Bologna, an unusual setting compared to the more traditional ones of Italian suburbs or the capital. She wears masculine clothes and displays an androgynous, sensual body; she uses men as pastimes but suffers for inspector Luca Bruni, played by Thomas Trabacchi, who disappointed and betrayed her many times. She lost her sister, and her anomalous family is composed of his younger, homosexual assistant, and a former porn star who manages the night-club where she performs. Family traumas make her a suffering and restless character, and increasingly acquire relevance in the running plot, while the anthology plot focuses on the case to be solved.

Ten years later, the first Netflix original Italian productions also belong to the crime genre. If Suburra (2017-) continues along the line of the transmedia model launched by Romanzo criminale and then further powered by the worldwide success of Gomorrah (2014-), the TV show Baby (2018-) focuses on the female point of view of two teenage protagonists to tell a story where the boundary between good and evil, victim and executioner, moral and immoral, becomes dangerously blurred and uncertain.

Between Sky and Netflix, between Quo vadis, baby? and Baby, production strategies of the two main Italian broadcasters also take advantage of the crime genre. In particular, the new production strategies developed by Rai Fiction, the production division of the Italian public broadcaster Rai, promote stories told from a woman’s point of view. Within these strategies, the detective story plays an important role and there is a very interesting mix between tradition (those well-established models needed to address to a wide audience) and innovation in narratives structures, characters development and the use of locations.

Between 2015 and 2019, inspector Valeria Ferro (Non uccidere, 2015-2018) appeared, followed by the resident in forensic medicine Alice Allevi (L’allieva, 2016-), adapted from the novels of Alessia Gazzola, and the deputy prosecutor Imma Tataranni (Imma Tataranni – Sostituto procuratore, 2019-), from the novels of Mariolina Venezia.

Non uccidere, co-produced by Rai Fiction with Freemantle, is a particularly innovative prime-time TV show and broadcast in Italy in a quite unusual way. The first season (12 episodes) aired on Rai 3, the third and most sophisticated public channel, from September to October 2015 (first part) and then from January to February 2016 (second part). The first part of the second season (24 episodes) was initially released on Rai VOD portal RaiPlay in June 2017, and then aired on Rai 2, the second public channel, from June to July 2017. Ratings were very low compared to similar Italian TV shows broadcast by the channel, and the second part (after the release on RaiPlay in December 2018) was then relocated on the niche channel Rai Premium from January to February 2019. Despite the bad reception in Italy, the show circulated quite well abroad – in France (Squadra criminale), Germany (Die Toten von Turin), and through the VOD service Walter presents (Thou Shalt Not Kill). In the backstage materials and interviews, the actors and the crew make explicit references both to the “Nordic” visual style of the show as a “disruptive” element in the Italian scenario, and to the relationships with the Scandinavian narratives featuring strong and complex women in the role of leading detectives.

The protagonist of the show is Valeria Ferro, a woman in her thirties and inspector of the homicide squad. Like Quo Vadis baby?, the series features an unusual urban setting (Turin, Northern Italy) and the actor Thomas Trabacchi, who plays the role of the protagonists’ lover in both the series. Yet, it is particularly interesting to observe that in Non uccidere the character played by Trabacchi is not just a colleague, but he is the protagonist’s boss, thus addressing the problem of asymmetrical romantic relationships in the workplace. Valeria Ferro is interpreted by the actress and beauty pageant titleholder (she won the Miss Italia 2008 beauty contest) Miriam Leone, who exhibits a sort of “denied” beauty and sensuality, masked by the absence of makeup and apparent negligence in the clothing, with masculine clothes. While she is younger than Angela Baraldi, as Angela she has no children and her family traumas, as in Quo vadis, baby?, acquire a great relevance in the running plot and make Valeria a gloomy, tough and lonely character, while permeating the whole narrative with an oppressive and anguishing atmosphere.

Imma Tataranni – Sostituto procuratore is a prime time TV show co-produced by Rai Fiction and ITV Movies, broadcast on the main and most popular public channel Rai 1 from September to October 2019 with very good ratings. The protagonist, interpreted by Vanessa Scalera, is the vice public prosecutor Imma Tataranni, a woman in her forties and a strong and incorruptible professional. Again, the story is set in another unusual, “peripheral” location, the city of Matera (Southern Italy).

Differently from Giorgia and Valeria, Imma has a nice family, a passionate relationship with her husband and an intense, conflicting relationship with her teenage daughter. In this respect, Imma seems to challenge the traditional “incompatibility of the cultural categories of woman and detective”. More interestingly, she is proud of her professional skills and career while, at the same time, questioning the “natural” correspondence between social institutions like family and marriage and the complex sphere of women’s desires: in fact, she develops an ambiguous relationship with her younger subordinate Ippazio Calogiuri, where professional respect, sense of guilt and passion are dangerously mixed.

Furthermore, Imma does not neglect her appearance as usually do strong female detectives, nor she passively follows fashion trends. She has a personal and eccentric dressing style, with kitsch pieces and unlikely combinations, which however Imma wears coolly, showing her self-confidence and her determined personality.

Finally, the prime time TV series L’allieva was created by Endemol Shine Italy and co-produced with Rai Fiction. The show, a carefully balanced mix between detection story, chick lit, and romantic comedy, tells the sentimental and professional life of Alice Allevi, interpreted by the popular actress Alessandra Mastronardi, a pretty girl in her twenties and a resident in forensic medicine. The first season, composed of 11 episodes, aired on Rai 1, the Italian most popular public channel, in September and October 2016, and the second season, 12 episodes, in October and November 2018, and it was a significant, popular success in Italy.

Alice, interpreted by Alessandra Mastronardi, is a curious mix between old and recent models of female detective. As a resident in forensic medicine, Alice seems to belong to the general type of the criminalist, who uses intelligence and specialized knowledge rather than combat skills. As a student, however, she cannot be considered exactly as a professional detective, and this of course is very important since female professional detectives were a rarity until the 1970s and indeed are a relatively contemporary achievement. In this respect, Alice seems therefore also correspond to the more traditional stereotype of the “naïve young woman”: a sensitive, clumsy but brilliant woman, a talented and yet still amateur detective with a “conventional” good feminine intuition that helps police to solve complex cases.

Three different elements sustain this interpretation. First, the writer Alessia Gazzola frequently refers to the legacy of golden age crime fiction, and especially of Agatha Christie; second, in Rai Fiction communication strategies is strongly emphasized that L’allieva is radically different from crime shows like Body of Proof, for instance, where medical examiner Megan Hunt is deeply engaged in solving cases; and finally, textual analysis on a narrative level allows to point out how often Alice’s supervisor Claudio Conforti reminds her that she has to analyze bodies, and forget to do investigations because investigation is not her job.

Furthermore, and differently from the prototypes of female professional detectives, like Sharon McCone and Kay Scarpetta in crime fiction, Clarice Starling in film and Dana Scully or Jane Tennison on TV, who continuously confront sexual discrimination at the workplace and in society, Alice seems to live in a “post-feminist” scenario, “a world in which feminism has been taken into account (everyone is aware of the discourses of equal opportunities and antidiscrimination)” (Turnbull). Although there are no female characters in the police, women prevail among the residents in forensic medicine who work with Alice and are also represented at the top of the Institute of forensic medicine.

Despite her eternal irresolution, Alice has many professional gratifications and no real doubts about her professional qualities. However, tricky questions about the representation and role of women continue to be largely present. And this consideration brings us to the relationship between crime and the romantic comedy or, in other terms, between love and detection.

Apparently, Alice could not be any more different from the Nordic Noir female investigators. Like her Nordic colleagues, in the professional field Alice is self-confident and aware of her abilities. However, she is definitely love-focused rather than job-focused. She does not neglect her appearance as do Nordic noir female detectives: she has a fresh and natural beauty and she is completely at ease with her “feminine” charm. Alice is continually and explicitly the object of male desire, but without this being a problem. She does not even need to “overturn” the stereotype of feminine charm to take advantage in investigations, for example by working undercover.

Although she knows what she wants for her professional career, it is love that involves her whole character and thoughts. References to the character of Bridget Jones and romantic comedy are frequently made in the press given the narrative dominance of romance, and more specifically the fact that Alice is undecided between two men. What is more, this “ménage a trois” is complicated by power relations: one man, Claudio, is her direct supervisor, and the other, Arthur, is the son of the director of the Institute.

When Kim points out that a “woman can hardly be both sexual and detective”, she specifies that this is because “her detective authority derives from the lack of male figures that influence her life in any meaningful way”. In fact, Alice’s personal and professional problems come specifically from love and men. Although there is no discriminatory framework in her work environment, the two men embody a conception of gender relations that may seem anachronistic.

Arthur is a young reporter who would like Alice to leave Rome and her job to follow him on his travels. Claudio gives her an ultimatum: Alice must choose between him and her job at the institute, as otherwise Alice’s professional success would forever be related to her relationship with a direct superior, rather than to her own skills. It could be said that, in this case, the issue is seemingly asymmetrical romantic relationships in the workplace, rather than gender relations specifically: and yet, can we claim that the fact that the superior is a man is really irrelevant?

However, at the end of the second season, although love remains Alice’s greatest romantic dream, it is precisely love that she seems to renounce to preserve her professional ambitions.

Like many other female detectives, Alice is an ambivalent character: she is simultaneously progressive in the “professional” sphere, but conformist in the sentimental sphere.

As Klein punctually observes, “almost all female detective shows on TV are both progressive and regressive, both empowering and disempowering to women, portraying the female detective as both capable and incapable”. Most female detectives on TV are marked by ambivalence and provide “modern yet safe” solutions to the divergences between the viewers’ expectations regarding the crime genre and the expectations regarding the representation of female identity.

Furthermore, the character’s ambivalence can be also related to the mix between the detection story and romantic comedy (along with chick lit). While the conservative dimension of Alice relates to the field of comedy, her most progressive features relate to her professional goals and the crime domain.

That said, the topic of the sympathetic heroine facing obstructed love is also tied to the very popular tradition of romantic melodrama – and indeed the series head writer Peter Exacoustos has strong expertise in the genre. Although many distinctive features of melodrama are mitigated by its combination with romantic comedy, whereby touches of humor lighten the feeling of moral injustice and the pathos, it is the melodramatic imagination, so deeply rooted and so powerful in Italian popular culture, that makes the romantic storyline so captivating and engaging. By endorsing the melodramatic ideal of romantic love, Alice conforms to social roles and expectations about gender that seem to remain deeply rooted in the Italian context, as the great popular success of the tv series demonstrates.

The list of female characters in contemporary Italian crime productions (or with a crime component) could be further enriched. Crime and the coming-of-age story are combined in the stories of Vanessa (La porta rossa / The Red Door, Rai Fiction-Vela film 2017-), a teenage medium who accompanies the ghost of Commissioner Cagliostro in the search for his murderer, and of the two girls we see growing and struggling in post-war Italy in L’amica geniale / The Brilliant Friend (Rai Fiction-HBO, 2018-), from the novels of Elena Ferrante.

Also the commercial broadcaster Mediaset has recently explored the field of female detection in the prime time series Il processo (Mediaset / Fandango 2019), with the character of Elena Guerra, a public prosecutor in her thirties struggling to reconcile the dedication to her job with her difficult marriage and the problematic choice of motherhood.

Giorgia, Valeria, Alice, Imma, Vanessa, Elena… Of course, the European territory of female investigators is far richer. It is sufficient to think about how successfully popular and innovative characters like Raquel Murillo from Spain (La casa de papel), Ellie Miller (Broadchurch), Kip Glaspie (Collateral), Stella Gibson (The Fall) or Kate Ashby (Black Heart Rising) from UK, Sarah Lund and Saga Norén from Denmark and Sweden, Jasmina Orban (La Trêve) from Belgium, Jeanne La Mante from France circulate. In our search for a transcultural and transnational European identity negotiated through popular crime narratives, the richness of the territory to be explored is evident. We just need to move on.