“A New Crop of Mom Thrillers Taps Into Our Worst Fears” declared an essay by Jen Gann published in February 2018. I had been trolling for information about crime fiction from the mother’s perspective to help shed light on my approach to three suspense novels by Argentine author Claudia Piñeiro that featured mothers who had failed their children. Gann’s essay, describing motherhood-themed thrillers, sent me into a tailspin, recalibrating my research focus. Tracking down further works belonging to this seemingly new subgenre I found a rich and varied trove of “mom thrillers” from around the globe, most published in recent years.

A little more probing and I found out that “motherhood is on trend,” at least according to Natalie Alcala who founded Fashion Mamas for mothers in the fashion industry. As if to confirm this assertion, four review essays published between April and July 2018 discuss the recent array of books about motherhood. For the most part, these essays treat what Laura Elkin considers “serious” books on motherhood. Only two make passing mention to thrillers, with Parul Seghal calling them “a genre grouped under the ghastly moniker ‘mom thriller’.” And yet mom thrillers beckon to readers—numerous are New York Times Best Sellers—and they offer incisive and compelling portraits of motherhood.

After searching, reading, and sifting out works lacking literary merit or failing to fit my criteria for the new subgenre (detailed below), I have identified nearly thirty mom thrillers published over the last three years: six published in 2017, twelve in 2018, and seven so far in 2019. My sleuthing confirmed that no one has set out a definition of the mom thriller and no one has engaged in a critical discussion of this subgenre. So here goes.

To be included in the grouping that I consider “mom thrillers,” the novel must be matrifocal, that is narrated from the mother’s perspective—at least in part—whether in first or third person. The mom thriller’s central focus has to do with the mother confronting a threat or danger to her child and, of course, it is a thriller. To understand and characterize that elusive category of “thriller,” I found most useful the work of Martin Rubin. The following are the aspects of the thriller that seem most pertinent to the mom thriller. First of all, there is an excess of certain qualities and sensations such as suspense, fright, and mystery with an emphasis on visceral, gut-level feelings. There must be a sense of extraordinary danger arising out of an ordinary situation, usually accompanied by a strong sense of contrast between two different dimensions—specifically the mundane and ordinary co-existing with a dark and mysterious realm that is eerie, uncanny, or frightening. Also key is the reader’s response. She or he is enthralled, captive, spellbound. Something is deliberately withheld from us: we are anticipating some revelation that keeps us turning the pages.

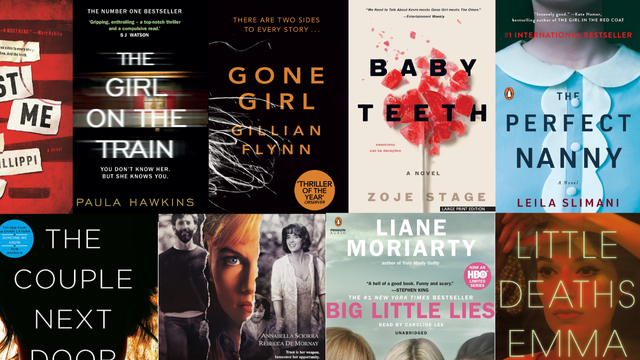

The mom thriller’s matrifocality is a significant departure from traditional crime fiction: when it evokes the mother figure, more often than not it is to account for the criminality of the murderous son. The iconic case is Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. The mom thriller has sister subgenres, which may or may not overlap with it: suburban noir, popularized by works such as Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train, and domestic suspense, a subgenre that can be traced back to the 1950s. Excluded from the mom thriller are daughter-centric narratives, the most well-known being the nonfictional Mommy Dearest, Christina Crawford’s shocking chronicle of abuse at the hands of her famous stepmother, actress Joan Crawford.

In their introduction to texts about motherhood, Elizabeth Podnieks and Andrea O’Reilly tell us that daughter-centric narratives—such as Christina Crawford’s—have dominated maternal traditions and a matrifocal perspective has emerged only over the last few decades. Their volume examines “how authors use textual spaces to accept, embrace, negotiate, reconcile, resist, and challenge traditional conceptions of mothering and maternal roles” (1-2). A central focus of their anthology is to bring to light texts that “unmask” motherhood, narratives that demonstrate the candor to admit ambivalence and anger. The mom thriller answers this call, delving into the trials and tribulations of motherhood.

What has brought about this surge in texts exploring the challenges of motherhood? Social observers point to a twenty-first century obsession with the ideal of perfection in motherhood. Psychologist Shari Thurer discusses the social pressures on mothers and the guilt feelings brought on by these expectations:

Our society has become unabashedly prenatal… Never before have the stakes of motherhood been so high—the very mental health of the children. Yet never before has the task been so difficult, so labor intensive, subtle, and unclear. … Media images of happy, fulfilled mothers, and onslaught of advice from experts, have only added to mothers’ feelings of inadequacy, guilt, and anxiety. Mothers today cling to an ideal that can never be reached but somehow cannot be discarded. (340)

As a psychologist I cannot recall ever treating a mother who did not harbor shameful secrets about how her behavior or feelings damaged her children….A sentimentalized image of the perfect mother casts a long, guilt-inducing shadow over real mothers’ lives…We have become highly judgmental about the practice of mothering, and especially about ourselves as mothers. (331)

Jacqueline Rose also speaks to the pervasiveness of this mindset and its pernicious effect on women:

We are now witnessing … a “neo-liberal intensification of mothering” – perfectly turned-out, middle-class, mainly white mothers, with their perfect jobs, perfect husbands and marriages, whose permanent glow of self-satisfaction is intended to make all women who do not conform to that image … feel like total failures. (17)

The appetite for certain fictions is symptomatic of broad cultural trends (Hollister 27), and mom thrillers may serve as a reaction against this cultural imaginary of maternal perfection. They explore the guilt Thurer has observed in her patients, the what-if scenarios that populate a mother’s worst nightmares. Danger always lurks—whether it is in the form of strangers, acquaintances, partners, freak accidents, or the mother or child themselves. Motherhood is messy and mothers are not perfect: they may suffer mental breakdown or simply exercise bad judgement. They may harbor ambivalence about having become a mother. Motherhood can be fraught with no-win choices. Social norms and the judgement of others may work against the mother.

While it seems foolhardy to say with certainty when the first mom thriller appeared, we can identify notable forerunners of the current miniboom from the last three decades of the twentieth century. Two consecrated women crime writers penned novels of suspense from the mother’s perspective. Mary Higgins Clark’s 1975 Where Are the Children? explores what society considers an aberration: a mother accused of killing her children. It was made into a 1986 movie directed by Bruce Malmuth and starring Jill Clayburgh. Ruth Rendell’s The Tree of Hands (1984) considers another topic that will reappear in twenty-first century mom thrillers: a mother-figure who kidnaps a neglected child to give him a better life. The psychotic nanny is treated in the 1992 film The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, made into a novel by Robert Tine.

I now turn my attention to the recent raft of mom thrillers—those published in 2017, 2018, and 2019. In order to approach them, I decided that a categorization according to their narrative scheme, or plot line would best illuminate their predominant concerns. The child’s disappearance, either by abduction or by death, is the most frequent plot line. Since protecting the life and well-being of one’s child is surely the fundamental aim of motherhood, the thrillers imagine the mother’s reaction when she confronts these unthinkable situations. Sometimes the mother is the agent or potential agent of this loss, as is the case in stories about murder-suspect moms and kidnappings carried out by moms. Another frequent theme is moms confronted with one another; in this scenario, the “underdog” or “flawed” mom ultimately gains the higher ground. Still another depiction is the mother whose devotion to her child leads her to commit a crime on the child’s behalf. And of course, there is the hysterical nanny who brings harm to her charge or charges. An exceptionally unsettling portrayal of motherhood is that of the mother who deals with an evil child bent on destroying her. Finally, there are redeeming stories about the heroic mom who takes extraordinary measures to protect her child. Some of these novels carry a political agenda, denouncing bullying, domestic violence, body shaming leading to anorexia, and the stigmatization of postpartum depression.

8 Best Mom Thrillers

Among this collection of portrayals of troubled maternity, I have selected the eight novels I consider the best, those that are masterfully executed, those that are hauntingly unforgettable. Perhaps the most well-known of the group is Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty, made into an HBO series. In this classic tale of the vindication of the underdog, we witness the striving for perfection among mothers of young children: “Mothers took their mothering so seriously now” (2%) reflects a grandmother. Thematic concerns include bullying among school children, competition between mothers who are fiercely protective of their children, domestic violence, and eventually, vindication and healing. The novel is set in an idyllic Australian beach town where lives and lies begin to unravel when a single mother with a secret mission moves in with her young son. The tale is told from the viewpoints of three mothers of kindergarteners: Jane, the single mother; Madeline, a glittery girly type who was jilted by her husband and has remarried; and Celeste, enviably beautiful with darling twin sons, a rich handsome husband, and the seemingly perfect life. In the beginning, we learn that something terrible happened on School Trivia Night. The narrative then jumps backwards in time to six months prior and each chapter draws us closer to discovering what happened. The voices of witnesses end each chapter reporting their version of events to the police, hinting at what transpired and building anticipation as that fateful night approaches. Moriarity writes with an easy style capturing the bitchiness that can emanate from the mothers of kindergartners but delivers a serious message about bullying and domestic abuse when the façades drop, and ugly secrets are revealed. The HBO series based on the novel explores in depth the lives of the characters, producing two entertaining seasons, a total of fourteen episodes. The setting has been moved to a California beach town, and big stars take the leads: Reese Witherspoon as Madeline and Nicole Kidman as Celeste.

The evil or psychotic nanny who harms her charges is an archetypal figure repeated in literature and film, touching a universal fear and projecting the mother’s guilt for relegating the care of her children to strangers. A mid-century version of that theme is Patricia Highsmith’s 1945 short story “The Heroine,” which depicts a young governess, who, unbeknownst to her employers, has been recently discharged from psychiatric care. An ominous mood builds to a horrifying crescendo via the young woman’s obsessive thoughts and her eagerness to demonstrate her devotion to the family. In The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, a psychopathic, revenge-seeking nanny seeks to win over the children and father and dispose of the mother, taking her place in the family. Leila Slimani’s version of the killer nanny, set in Paris, was inspired by a horrific event that took place in 2012: a New York nanny killed the two children in her care because she was angry that she had been asked to take on cleaning duties. Slimani’s novel The Perfect Nanny, originally published in French as Chanson Douce, has obtained international acclaim. It has been translated into thirty-five languages and earned its author a review article in The New Yorker on the eve of its publication in English. The novel opens with the “perfect nanny’s” cold-blooded murder of the two small children in her charge, and then backtracks to develop a sociological and psychological picture of the circumstances that lead up to the nanny’s breakdown. An upper-middle class couple, Paul and Myriam, hire Louise to care for the children because Myriam, after an initial period of elation with being a stay-at-home mother, wants to return to her profession as a lawyer. Louise voluntarily takes on more and more household duties, which she performs with perfection, and Myriam sings her praises, becoming increasingly dependent on her. As critics note, the novel fleshes out the “complex and ambiguous relationship” that comprises a family and their nanny, “at once intimate and subservient” (Collins 3, Sacks). Reflecting Rose’s aforementioned observation of a recent trend, Laura Collins maintains that the novel delivers a devastating critique of the “neoliberal intensification of mothering”: “Slimani tries to put a price on the anxieties, hypocrisies, and inequalities that arise from the commodification of our most intimate relationships” (2). Maureen Corrigan, on the other hand, points to the story’s latent psychological message, attributing its success to “the enduring masochistic power of that nightmare of maternal inadequacy.” Sparse and precisely written, this novel about the problematic relationship between a nanny and her employers that culminates in unspeakable tragedy is disquieting on both a sociological and a psychological level.

Next come deftly-plotted and twisty takes on the kidnapped child: The Couple Next Door by Shari Lapena and Good As Gone by Amy Gentry. While the circumstances of the kidnappings in the two stories are completely different, what the novels have in common is that both mothers blame themselves for the abduction of their daughters, accusing themselves of not being good mothers. The Couple Next Door –about a baby’s disappearance from her upstate New York home—was a bestseller, having sold more than 50,000 copies. The precipitating situation is set up when parents Anne and Marco are invited for dinner by the couple next door and the babysitter is not available. The couple is not child-friendly, and Marco convinces Anne that it will be alright to leave baby Cora sleeping at home. After all, it will only be a few hours and they will be next door with the baby monitor. Right? Wrong! The baby is kidnapped. Anne feels agonizingly guilty: “Who goes to a dinner party next door and leaves her baby alone in the house? What kind of mother does such a thing? She feels the familiar agony set in—she is not a good mother” (3%). She is sure that she will be judged for leaving her baby alone—judged by the police, by other mothers in her group, by the public when it becomes a news story. On top of that, when it is revealed that Anne struggles with postpartum depression and was not coping well, it sets off the suspicion that she was involved in the baby’s disappearance. Even Anne begins to fear that she actually did something to harm her baby. But the plot takes another turn when the police probe for a motive and Marco brings up the fact that Anne’s parents have a lot of money. Is this going to be a Fargo-like plot where the husband abducts a family member to extort his father-in-law? The wonderfully suspenseful and convoluted turns of events and revelations keep the reader turning the pages as we read on to discover what happened to baby Cora. Besides being a satisfying and edge-of-the-seat read, this novel offers a sensitive examination of postpartum depression.

Good As Gone by Amy Gentry is a complex and subtle story that has to do with a mother’s failure to recognize her daughter’s deep-seated spiritual needs. When Julie is thirteen, she is kidnapped from her home at knifepoint. Eight years later, a very much altered Julie shows up at the front door, claiming to have been a victim of human trafficking. But Julie’s story does not quite add up and her mother, Anna, begins to wonder if the young woman is an imposter pretending to be Julie. The narrative rotates between the first-person voice of Anna and the series of personas Julie has had to become in order to survive. Religion plays a prominent role in the plot, as Anna secretly follows the mystery girl to a megachurch led by a charismatic pastor, and it turns out that young Julie longed for a total surrender to God. Anna, an English professor who has no use for religion, realizes that she did not know her daughter at all:

I try to remember Julie asking me about God, but I can’t. Who was I, what was I doing that I can’t remember? I was finishing up a postdoc, then interviewing for jobs. (88%)

“How could I have been so blind? How could I have missed all that? It’s like I didn’t know her at all… I mean—I thought everything was good. I thought I was a good mother.” (91%)

Once again, the primordial emotion of the mom thriller is guilt, as Anna realizes Julie’s search for transcendence—that Anna was too wrapped up in her own career to notice—led to Julie being prey to a predator.

Hank Phillippi Ryan’s and Emma Flint’s novels, Trust Me and Little Deaths, respectively, treat mothers suspected of killing their children. These two murder-suspect mom novels depict social prejudices that cause the public to prejudge the defendants, proclaiming them guilty in the court of public opinion. The media’s eagerness to sell a titillating story of a monster mother to a rapt public plays a central role in both stories. Both are inspired by actual cases: Ryan’s novel has parallels to the Casey Anthony case while Flint’s is based on the 1965 murder trial of Alice Crimmins, accused of killing her two small children.

Trust Me is narrated from the perspective of Mercer Hennessy, a journalist whose life was shattered after her husband and three-year-old daughter were killed in an automobile accident. Trying to help her overcome depression, Mercer’s editor assigns her to write a true-crime book about Ashlyn Bryant, a young woman who is about to go on trial for killing her two-year-old daughter. Mercer, along with the rest of the public, is convinced that Ashlyn is guilty as hell; she calls her “the most reviled woman in Massachusetts, in the entire country, possibly” (3%). And, as a matter of fact, the success of Mercer’s book depends on Ashlyn’s guilt and the public’s hatred of her: “We can’t sell a book about a contrite and remorseful victim of postpartum depression,” says Mercer’s editor (11%). The news reports zero in on Ashlyn’s nightclubbing and publish a photo of her in a wet T-shirt, portraying a sex-pot mother who killed her child because she was an impediment to her partying. However, when Mercer begins to doubt that Ashlyn was responsible for her daughter’s death, and we learn details about the fatal accident that took Mercer’s husband and daughter, convictions about guilt and innocence are shaken up. “Hating Ashlyn is so much more rewarding than hating myself” (10%) admits Mercer, providing insight into our need to vilify others.

As mentioned above, Little Deaths by Emma Flint is based on a real-life murder trial. In the summer of 1965, two small children went missing from their bedroom in Queens and were later found dead. Their mother, Alice Crimmins, was separated from her husband and working as a cocktail waitress to support them. She became the chief suspect in their murders even before their bodies were found. Why? Because she did not conform to social norms of how a mother should behave. She worked long shifts in a seedy bar and locked her children in the bedroom while she slept late. She dressed provocatively, wore a heavy mask of make-up, drank and had multiple lovers. Crimmins was found guilty based on circumstantial evidence and imprisoned.

Emma Flint was fascinated by the Crimmins case, and hers is its tenth reworking. The novel focuses on the character assassination of the mother, named Ruth Malone in Flint’s version. In the real-life case, despite Crimmins’s vivid presence in the tabloid photos Flint observes that “she is strangely absent from each picture. Eyes cast down, lips pressed tight together, she refuses to look into the camera, refuses to engage with the audience” (Flint, “Fact and Fiction”). The novel captures this reticence, portraying Ruth mainly through the judging and disapproving eyes of others, but gives us occasional glimpses of Ruth’s subjectivity hidden beneath a mask of make-up and pride. A third person narrator provides her intimate thoughts, describing her grief: “It came to her as heaviness. It came as a stone in her throat, preventing her from swallowing; as a pressure behind her eyes, forcing out tears; as a weight in her stomach. It meant that she could not breathe. That she could not have a single moment of not remembering” (90). Flint describes Ruth’s silence resistance to the abusive, judgmental police officer at her trial:

“Maybe you stayed in the other room while he did it. While he silenced them. While he took them outside. Maybe all you’re guilty of is taking another hit from the bottle and turning the radio up. Is that how it was, Mrs. Malone?”

She bowed her head. He knew nothing about guilt. He knew nothing about leaving your kids alone or with a teenage sitter while you went out to work eight hours on your feet in a pair of heels that rubbed, serving drinks to assholes who thought they were buying the right to paw you with every round. (222)

The novel underscores the social pressure and prejudices of a working-class neighborhood in the 1960s and the opprobrium gained by a woman who does not look and behave as police officers and her narrowed-minded neighbors believe a mother should. The glimpses of Ruth’s subjectivity reveal her tender thoughts for her children and her feelings of guilt for what she had to do to provide for them. Critiquing the limited roles prescribed for women in US society of the 1960s, Flint provides a sympathetic portrait of a woman judged a “bad mother” because she did not conform to these norms. Both novels explore sensationalized real-life cases of mothers accused of killing their children, focusing on public shaming and the rush to judgement.

For an uplifting story about an intensely devoted mother, turn to Fierce Kingdom by Gin Phillips. While it narrates a terrifying ordeal, at the same time it is a celebration of positive mothering. Joan and Lincoln, Joan’s precocious four-year-old son, are exiting the zoo at dusk when Joan hears a popping sound, sees fallen people, and realizes there is an active shooter. She heaves her son up onto her hip and runs back into the zoo, searching for a hiding place. The novel unfolds in three hours in the zoo while the shooter or shooters roam about looking for people to shoot, and the mother and son’s survival depends on her keeping the four-year-old appeased and quiet. Joan is an intensely dedicated and involved mother, and the narrative highlights the exceptionally strong bond she has formed with her son: “She knows she has followed some pale thread from her brain to his. There are a million of these threads between them, brain to brain” (97%). Joan uses her minute knowledge of Lincoln and how he will react to every situation, along with her physical strength and problem-solving skills, to keep him from harm. Joan’s interior monologue, as she reflects on her dilemma as well as her relationship with her mother, husband, and son, provides the bulk of the narration, but we also hear the thoughts and voices of the shooter and others who are trapped in the zoo. This is a poignant portrait of how a mother’s fierce love and courage protects her child from danger and at the same time the novel explores women’s roles as mothers, spouses, and children.

Finally—my favorite—a masterfully executed tale of an evil child: Zoje Stage’s Baby Teeth. If this novel doesn’t give you the chills, nothing will. The best adjective to describe Baby Teeth is “creepy”—it’s both terrifying and wickedly funny at times. Hanna is a diabolical seven-year-old nonverbal child and her mother, Suzette, is at her wit’s end trying to deal with her. The novel is narrated in third person, rotating evenly between Hanna and Suzette, so we have access to the thoughts of both the child and mother as they engage in a battle of wills. Suzette vows to be a loving and attentive mother, everything that her depressed and uncaring mother was not. However, she is wracked with guilt about her ambivalent feelings toward motherhood. It becomes apparent that despite her best efforts Suzette is ill equipped to parent a difficult child like Hanna, and Hanna knows it. She senses her mother’s ambivalence: “Hanna felt it, how Mommy couldn’t relax with her in her arms. How Mommy wanted to drop her” (40%). She tests her mother and acts out in increasingly malevolent ways from tampering with her mother’s medication, to cutting off a big chunk of her mother’s hair while she sleeps, to trying to set her mother on fire. This cunning and manipulative child behaves sweetly in her father’s presence—father and daughter adore each other—and Hanna considers her mother a rival for his love and attention.

Hanna has been expelled from five schools, so Suzette has to home-school her, and we watch the parents’ frantic attempts to find a solution for the seemingly sociopathic child. The novel explores the trials of parenting a child such as Hanna and we witness the ambivalence Suzette feels: “The fear that motherhood had been a terrible mistake, the guilt that she wanted to undo it but couldn’t” (42%). A central question the text raises is how much responsibility Suzette bears for Hanna’s aggressive behavior. A portrait of a mother in crisis, we see the deleterious effects of motherhood on Suzette’s self-worth, her marriage, and her health, along with her ambivalence, guilt, and her regret for having become a mother. A deeply unsettling story, Baby Teeth takes normal parental anxieties to extremes. It represents the culmination of the “mom thriller.”

Author C. L. Taylor speculates that thrillers of this sort may be of comfort to readers: “Domestic Noir novels tap into our base fears… Confronting these fears in a psychological thriller can be cathartic.” So, do mom thrillers serve to help release the guilt and anxiety mothers may feel, reassuring them that their feelings are not abnormal? Or rather, do these novels wallow in the dark side of humanity, portraying irredeemably failed mothers and the lack of solidarity among women? Do they critique a judgmental society that marginalizes a mother who does not conform to narrow expectations of maternal behavior? Are they effective in promoting important political agendas, denouncing problems such as domestic abuse, bullying, the stigmatization of postpartum depression, and issues related to race and class?

As the above discussion demonstrates, there is not a unifying narrative pattern or thematic thread linking these novels; rather mom thrillers transmit a wide gamut of messages and emotions related to motherhood. While a few portray maternal empowerment, others depict the mother’s criminal deviance, and the majority explore the mother’s vulnerability and enact masochistic fantasies of loss. What they do have in common is that their noir perspective affords a complex exploration of female identity as it relates to women’s role as a mother. Engaging and enacting the many pitfalls that real mothers fear or confront, mom thrillers critique and subvert the ideal of maternal perfection.