In a famous essay, The Simple Art of Murder, published many years ago, Raymond Chandler characterized the classic, mostly British detective novel, the whodunit, as a form that has “learned nothing and forgotten nothing.” In a limited sense, he was entirely correct, though of course he was also arguing in favor of the kind of writing he practiced so brilliantly, what came to be called the hard-boiled detective novel. Oddly enough, despite Chandler’s disapproval, the formal detective novel continues to flourish alongside its hard-boiled counterpart, and continues to attract readers by the millions all over the world.

Both forms also manage to make the transition from verbal to visual media, as cinema and television exploit a variety of possibilities in detective fiction, often changing such elements as plot, character, and what might be called methodology. Although Chandler doubted that the classic techniques of close observation, rigorous logic, and brilliant deduction could achieve a great deal of success in film, history has in fact proved him wrong. Sherlock Holmes, for example, continues to undergo countless reincarnations in both television and cinema, assisted especially by American public television, which tends to deal heavily in British shows of various kinds. (There will always be an England, as long as there is a PBS).

Beyond and after Sherlock Holmes a long line of British detectives appear on the television screen, solving so many crimes, especially murders, that one wonders if whole villages in the United Kingdom have been decimated or even emptied of citizenry. To begin with the staples stretching back to the early years of the 20th century, Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple and, especially, her Hercule Poirot appear in several series of adaptations. David Suchet’s brilliant impersonation of Poirot and the meticulous recreation of the Belgian sleuth’s temporal context—the clothes, the cars, the architecture, even the art deco furnishings of his apartment—place that production far above both other attempts at translating Christie’s works to a visual medium and rank the actor far above his peers. Suchet’s impeccable interpretation of Poirot and the visual quality of the productions account for a good deal of their success.

Perhaps the most significant transformation of the British detective from verbal to visual narratives, however, has attracted little in the way of critical attention. The brilliant, often eccentric amateur, the effete dandy, whether Hercule Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey, Mr. Campion, or any of the numerous others who kindly help the police to solve mysterious crimes, tends to disappear from both television and cinema screens, replaced by a professional detective. In the English interpretations of that figure and his or her activities, however, a strong connection to the classic form remains visible and even vibrant.

Possibly in part because of their origin in fiction, many of the most popular television adaptations depend upon the familiar formulas of the past. The professionals often operate in the same small towns or discrete areas of England’s green and pleasant land as in the novels and stories, places populated by the usual suspects—vicar, military man, young wastrel, ingénue, grumpy old man, etc.—only without the assistance of any amateurs. The investigations of Reginald Hill’s Dalziel and Pascoe, Caroline Graham’s Inspector Barnaby, and Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse, for example, despite being the work of professional policemen, often resemble those of the great British traditions, and the policemen themselves especially demonstrate the sort of individuality associated with all those fictional sleuths.

The proliferation of British detective programs on television demonstrates the continuing appeal of the form and perhaps a touch of the Anglophilia that characterizes a certain segment of the American public. Among the seemingly innumerable examples, such titles as “Luther,” “Wire in the Blood,” “Foyle’s War,” “London Kills,” “Single-Handed,” “Shetland,” “Vera,” “Queens of Mystery,” and scores of others suggest the great variety, often of region and landscape, that those shows offer; a good many belong to the category known as cozy, with enough quaintness and twee to coat a crumpet. The British these days generate an apparently endless flow of television detectives, enlivening the concept with a wide variety of possibilities. The shows employ, for instance, black detectives, Irish detectives, Scottish detectives, Welsh detectives, Australian detectives, female detectives both amateur and professional, priest detectives (the Father Brown series), gardening detectives (“Rosemary and Thyme”), possibly ad infinitum, in a diversity that may continue to entertain forever.

Probably the most engaging of all the British sleuths in all the many shows is Inspector Morse of Oxford, wonderfully played by John Thaw. A great success all over Europe and North America, the series has won millions of fans, inspired not only a sequel and a prequel, but also a documentary, and energized tourism in Oxford, Wordsworth’s city of dreaming spires. Morse’s love of music, literature, and alcoholic beverages, his usually failed romances, his several eccentricities, add to a character with some of the traditional, defining traits inherited from Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin and above all, Sherlock Holmes. Inspector Barnaby, who works in the obviously murderous village of Somerset, probably follows Morse in popularity, and differs from the tradition in enjoying actual family life, a departure from tradition but also a nod to realism. The fat, loud, rude, flatulent Dalziel, played against the university educated, sophisticated Pascoe, for example, functions as a consciously oppositional brand of detective, clearly intended to counter the tradition of the gentleman amateur; at the same time his presence signals that a new sort of detective now and then works in television version of the form.

Other, more annoying professional policemen in the English mode quite simply defy plausibility. Adapted from the novels of P. D. James, the character of her Inspector Adam Dalgliesh is not only a policeman but also a poet, a rather unlikely combination that results in the principal actor mooning around with an anguished sadness on his face, displaying a truly offensive sensitivity. Perhaps because the author is an American, the series based on Elizabeth George’s novels seems even more preposterous, since it features the most aristocratic of all fictional policemen, Inspector Lynley, the 8th Earl of Asherton. Clearly the fictional and cinematic depiction of professional policemen displays a regrettable debt to the Golden Age exploits of the ineffable Lord Peter Wimsey, suggesting that despite the march of history, little has actually changed in British interpretations of the detective and detection, or, to quote Chandler again, they have learned nothing and forgotten nothing. In general, the British television detectives, even if they are not members of the nobility, retain a certain gentility, a measure of at least upper middle class status.

As for film, Chandler demonstrated both understanding and prescience in his belief that the classic detective novel translates poorly to the big screen, in part because the accumulation of clues, the interrogation of suspects, and most of all, a plot dependent on the solving of a puzzle at the end of the action will not grip film audiences. The movies that employ the classic formulas usually, as a result, employ other means to make their puzzles interesting and “cinematic,” thus the colorful and often comical series of movies starring Peter Ustinov as a fat and rather silly Poirot. Probably the most entertaining of all the many Agatha Christie adaptations, Murder on the Orient Express (1974), with Albert Finney as the Belgian sleuth, depends upon its glossy, stylish attention to the costumes and settings of the 1930s and the presence of a number of famous and accomplished stars, including Richard Widmark, Lauren Bacall, John Gielgud, Sean Connery, and Ingrid Bergman.

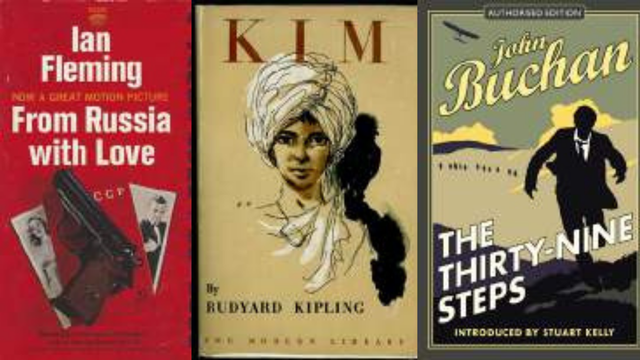

The detective films (and television shows), most of them based on fiction, that most naturally succeed, as Chandler suggested, are those that employ the people and actions of the American private eye novels. Innumerable television series over several decades show the adventures of Peter Gunn, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Lew Archer, Mike Hammer, and dozens of others. Rather than intricate puzzles to be solved by some mastermind, those programs depend upon a mixture of violent action, eccentric characters, and a tough private detective, all presented with a certain irony. The films in particular also depend upon an engaging leading man as the protagonist, a role occupied by many stars—Dick Powell, Humphrey Bogart, Robert Mitchum, James Garner, Paul Newman, among others. The part demands physical presence, the projection of virility, and at least a touch of wit, all of which work well on both the big and little screen. The scores of films based on either specific detective novels or upon the totality of the form and its people far outnumber the adaptations of the classic whodunits.

In recent years, however, the detective in television and film has moved in a different direction, employing different means, working in different ways. For the last half century, most of the many television series and films devoted to crime and crime solving depend not only on professional policemen but on the methodology of investigation. The police procedural now occupies the top position in numbers and popularity in both cinema and television; it is not so much a whodunit as a howcatchem.

The reasons for the dominance of the police procedural probably derive from the changes in culture and in history itself, particularly in America, which after all has dominated detective fiction for some decades now. Differing from the mostly polite and genteel investigators of the British form, where picturesque hamlets inhabited by kindly country folk appear to constitute the principal locales for murder, the American shows generally focus on urban crime. If only because of the size of its population, the city of course provides the natural setting for crime; murders occur every day in large cities all over the world at a scale that would depopulate any number of charming English hamlets.

In keeping with its urban setting, the contemporary version of the detective story generally involves not a single crime solver, but a group—a squad, a division, a bureau, a police force; as in what we like to think of as real life, police work, like many other government activities, demands group effort, even at times a massive bureaucracy. That group effort must include not only a particular investigator, but also a number of other people—crime scene analysts, technicians, experts in various fields, scientists, pathologists, etc. The group must also consult with the legal departments of law enforcement, chiefly the offices of the district attorneys and judges in whatever municipality a crime occurs, which of course diminishes the importance of the lone detective.

The procedural, as its name implies, deals with the actual nuts and bolts of police work, minus the magnifying glass, the relentless application of the little gray cells, the brilliant leaps of imagination. Instead it depends, as the name suggests, on the process itself, the gritty realities of police methods, which in our time means scientific and technological expertise, laboratories, machines, experts in all sorts of disciplines, from forensic dentistry to entomology. Ironically, present day investigative techniques, real or fictional, echo those of Sherlock Holmes in their concentration on minutiae, their use of scientific methods, their focus on hard evidence of all kinds. The proliferation of documentary televisions shows about various difficult and/or notorious criminal cases reinforces the audience’s awareness of the formidable machinery of contemporary law enforcement; more simply, many programs show the day-to-day work of police officers, which of course is rarely dramatic and rarely mysterious.

True crime influences the depiction of fictional crime in both television and cinema, however, and in many instances, the process of investigation overlaps, so that the true crime and fictional crime can sometimes seem indistinguishable. Add to that the numerous cop shows, both documentary and created, that concentrate mostly on the workings of uniformed and plainclothes policemen in normal contexts. For all the fictional programs about official law enforcement—“CSI,” “NCIS,” “Law and Order,” “Closer,” among others—dozens more nonfiction series cover much of the same material—“Crime 360,” “Manhunt,” “Hometown Homicide,” “Forensic Files,” and so on. Though the debt is seldom acknowledged, all these shows descend from the legendary police series “Dragnet,” which introduced some of the methods, the insider attitudes, and even the language of detective work, often through the speech of the laconic Joe Friday, way back in the 1950s. The public’s appetite for a kind of documentary gore apparently seems unlikely to diminish, especially since in America the cable channels and the special streaming services mingle even more true crime with their detective fiction. In addition, American film especially excels at process, the sheer narrative of showing the sequential details of a particular task, whether building a barn, as in Witness, creating a baseball bat, as in The Natural, or the examination of video surveillance footage, as in Blood Work. That fascination with process accounts for the popularity of such television shows that do not involve detection as “Forged in Fire” and “How It’s Made.”

Like television, the cinema also generally tends to focus on the professional detective, although the medium also maintains the romance of the private eye, providing more of a sense of a mystery to be solved. The form employs a far more appropriate and attractive protagonist than the ordinary cop show, usually accompanied by a cast of characters and the kind of action that Americans prefer—sexually attractive women, tough thugs, physical violence. The long heritage of such films as The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, Murder, My Sweet, The Long Goodbye and dozens of others influences scores of later films, and many in effect pay tribute to that tradition in small and large ways. In The Late Show (1977) Art Carney plays a retired private eye so deeply stuck in the past that he charges the same rates as Bogart back in 1946. The unimpressive office that Philip Marlowe occupies in The Big Sleep (1946) returns in a color version in Marlowe (1969), a film based on Raymond Chandler’s The Little Sister, with James Garner playing Marlowe this time. (Bruce Lee, incidentally, destroys that office in a famous comic scene).

Perhaps the best American detective movie ever made, Chinatown (1974) retains some of the elements of its genre, but departs somewhat from the romanticized image of its protagonist. Although Jack Nicholson, who plays Jake Gittes, the Los Angeles private detective, lacks the wit and the occasional charm of several of the actors who have played Philip Marlowe, he inherits some of their wise guy quality, especially in his running conflicts with the police. His actual methods of detection, unlike those of his cinematic predecessors, demonstrate a genuine sense of procedure, rather than the often simply linear progress of many traditional films, in which the protagonist moves through series of scenes, confronts a series of characters, and often encounters violence. Jake tracks the histories of suspects, visits witnesses, uses some rather primitive devices, like placing a cheap watch under the tires of cars to determine the time when a suspect leaves a location. Since the picture is set in the 1930s, those crude but ingenious devices seem perfectly appropriate for the time and place.

More important, the film also follows another branch of the genre’s tradition in its focus on relationships beyond the familiar instance of the detective falling for an attractive female client. If the gangster film is so often a brother movie, the hard-boiled detective film is a sister movie. The Maltese Falcon begins with Brigid O’Shaughnessy (aka Miss Wonderly) hiring Sam Spade and Miles Archer to deal with a villain who has apparently seduced her sister. In dealing with the Sternwood family in The Big Sleep, Philip Marlowe encounters two sisters, Vivian and Carmen Sternwood, who occupy important and ultimately sinister roles in both the novel and the film. Again, based on Chandler’s novel The Little Sister, the 1969 Marlowe revolves around the actions of two very different sisters, the actress Mavis Weld and her little sister, Orfamay Quest, from Manhattan, Kansas. Probably the ultimate hard-boiled sister movie, Chinatown provides a shockingly different take on sisterhood, using the corruption of incest as an appropriate accompaniment to governmental and corporate corruption.

In recent years, though the traditional private eye seems to have left the television screen, he occasionally reappears in the movies, sometimes in rather untraditional ways. In The Conversation (1974) Francis Ford Coppola in effect reinvented the private detective, turning him into a surveillance expert and security consultant, employing sophisticated electronic devices to eavesdrop and film a couple for a corporate bigwig. The movie shows the fascinating details of just how the protagonist captures an audio and video recording and then clarifies and amplifies the dialogue, the conversation of the title, to interpret its meaning. Like his predecessors, he becomes involved with the people he investigates, although in a significantly different way, with a drastically different outcome. He discovers that in effect he has been investigating the wrong people for the wrong reasons, that his own guilt has led him to a tragic defeat. Another variant on the form, he science fiction film Blade Runner (1982) shows some of the methods a detective named Deckard employs to track down a trio of replicants—artificially created pseudo-humans—in 2019, with a fascinating sequence in which he uses a computer to analyze a photograph; as in The Conversation the detective finds out a good deal more than he intended, with ambiguous consequences for himself.

Finally, although the possibility exists in certain post-modernist writing, the detective story rarely ventures into the territory of metafiction. One of the best examples of that possibility, however, uses both the element of the supernatural and a plot that might easily come from any of the French New Novelists. In Angel Heart (1987) the private eye, sent on a search for a missing former soldier, finds that he is actually seeking (and finding) himself. The film provides a suitable conclusion to the rich history of cinematic detection, one that may point toward a future of further experimentation. Despite more than a hundred years of formulaic patterns, familiar characters, puzzling problems, and memorable investigators, the form may yet, to reinterpret Chandler’s words, learn something and forget something.